Every year, I like to close out this newsletter with a roundup of passages from the books I read during the year that made an impression on me. This isn’t a “best of” list, and it’s not all the books I read — like last year, I’m sticking to dead authors only. Here are my collected passages from last year, from 2022, and 2021 (part one, part two). These appear in roughly the order I read them.

Embers, by Sandor Marai

The bulk of this melodramatic but highly readable 1942 novel consists of a monologue by the General, who has prepared for many years to confront a friend-turned-enemy about an incident from their shared past. He wants to pose a specific question, but in the long process of trying to articulate the question, he grows more and more uncertain of his project. He realizes that he no longer cares about the answer, that he already knows everything important, but that his long years of waiting will have been meaningless if he can’t bring himself to the moment of confrontation:

For forty-one years my life has been suspended between an everything and a nothing, and the only person who can help me is you. I do not wish to die like this… Everything else is mere words, deceptive shapes: ‘lies,’ ‘love,’ ‘misdeeds,’ ‘friendship, all of them pale under the intense light of this question, bleached of life like the bodies of the dead or pictures subject to the ravages of time. None of it interests me anymore, I have no desire to know the truth about your relationship, any of the details, the ‘hows’ and the ‘whys.’ I do not care. Between any two people, a woman and a man, the ‘hows’ and the ‘whys’ are always so lamentably the same . . . the entire constallation is despicably straightforward. ‘Because’ and ‘like that’—something could happen, something did—that is what makes the truth. Finally there is no sense in investigating the details. But one has an obligation to seek out the essentials, the truth of things, because otherwise, why has one lived at all? Why has one endured these forty-one years? Why, otherwise, would I have waited for you—not in your guise of a faithless brother or a runaway friend but in mine of both judge and victim, expecting the return of the accused? And now the accused is sitting here, and I pose my question, and he wishes to answer. But have I posed it correctly, have I said everything he needs to know, as both perpetrator and accused, if he is to speak the truth?

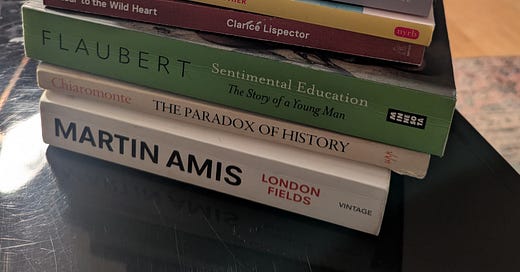

The Paradox of History, Nicola Chiaromonte

My post about this essay collection was one of the most popular I wrote this year. Chiaromonte sets about the task of trying to understand the nature of history — what is it? What can we say “causes” historical events, when we no longer believe in God or Fate? — through select works of literature by Stendhal, Tolstoy, and others.

From a passage in the essay Summer 1914 about Les Thibaults, discussing the assassination of Juan Juarès and the effect it has on one of the characters of the novel:

After such an event as the assassination of Juarès, what is left of the confidence in the accord between human aspirations and the course of history? The reasons to trust the future of society are certainly shaken. If social life, instead of becoming an insurance against the hidden forces in man and in nature, becomes the place where such forces are let loose; and if the individual, instead of finding in it reason for hope, comes up against a blind impersonal fate, then the social contract is broken, or so it seems.

At that moment, the individual finds himself as much of a stranger in the face of the effects of human actions as in the face of nature. With the difference that it is not possible to resign oneself to the evils of society in the same way as one submits to the adversity of nature. No matter how far we push the idea that human vicissitudes are governed by fixed laws, we will never be able to admit that society is ruled by a necessity similar to physical necessity. The thought will obstinately persist that “if men had wanted to, this might not have happened . . .” But, precisely, men have not wanted, not known how, or not been able. Why? Because they were what they were. The idea that the course of events depends, in the last analysis, on the will of men expresses the way in which fatality manifests itself in the human world.

Being as it is, an effect of human actions, the historical event lets us perceive dimly a law far more enigmatic than that governing nature. It is a law which one obeys no matter what one does, since it regulates both the rhythms of nature and the secret springs of human will. And it is an utterly baffling law in that it leaves us free.

A Way of Life, Like Any Other, by Darcy O’Brien

I briefly discussed this loosely autobiographical novel in a previous post: a coming-of-age story about a boy growing up alternately spoiled and neglected by his parents, both of whom are washed-up minor movie stars. It includes this ironic description of the sculptures of Anatol, one of his mother’s post-divorce lovers:

Anatol was hardly the first Western artist to take as his theme the presence of the human in the divine and the divine in the human, but his genius produced twists and nuances to what in cruder hands could have been dull, cliché-ridden, journeyman’s work. His “Zeus Assaulting Athene,” for instance, suggested far more than the obvious quest for union between the principles of creation and knowledge. The work achieved its effect of surprise and antic abandon through a single daring leap in construction: the goddess was five times the size of the father of the gods, who, captured in the act of scrambling up the female buttocks, reflected in every straining sinew the desperation of a man who may have taken on a task too big for him. “Will he attain it?” was the question scupturally posed. And in the eyes, beetle-browed and bulging with determination, lay the answer, “Yes.”

Despair, Vladimir Nabokov

Despair has many similarities to the much more famous Lolita (which I also re-read this year): it is structured as the first-person confession of someone who has committed a terrible crime. In his preface, Nabokov writes that the narrator of Despair is even less redeemable than Humbert: “Both are neurotic scoundrels, yet there is a green lane in Paradise where Humbert is permitted to wander at dusk once a year; but Hell shall never parole Hermann.” He plays a little with the “confession” conceit here, with his narrator Hermann imagining the Russian émigré who might one day publish his writing under his own name:

Having at last made up my mind to give my manuscript to one who is sure to like it and do his best to have it published, I am fully aware of the fact that my chosen one (you, my first reader) is an émigré novelist, whose books cannot possibly appear in the U.S.S.R. Maybe, however, an exception will be made for this book, considering that it was not you who actually wrote it. Oh, how I cherish the hope that in spite of your émigré signature (the diaphanous spuriousness of which will deceive nobody) my book may find a market in the U.S.S.R.! As I am far from being an enemy of the Soviet rule, I am sure to have unwittingly expressed certain notions in my book, which correspond perfectly to the dialectical demands of the current moment. It even seems to me sometimes that my basic theme, the resemblence between two persons, has a profound allegorical meaning. This remarkable physical likeness probably appealed to me (subsconsciously!) as the promise of that ideal sameness which is to unite people in the classless society of the future; and by striving to make use of an isolated case, I was, though still blind to social truths, fulfilling, nonetheless, a certain social function… Therefore I do think that Soviet youths of today should derive considerable benefit from a study of my book under the supervision of an experienced Marxist who would help them to follow through its pages the rudimentary wriggles of the social message it contains. Aye, let other nations, too, translate it into their respective languages, so that American readers may satisfy their craving for gory glamour; the French discern mirages of sodomy in my partiality for a vagabond; and Germans relish the skittish side of a semi-Slavonic soul. Read it, read it, as many as possible, ladies and gentlemen! I welcome you all as my readers.

Herzog, Saul Bellow

This is one of many moments in which professor Herzog, obsessed with his ex-wife and entertaining/repulsing the affections of the too-eager Ramona, contemplates his own ridiculousness.

He exclaimed mentally, Marry Me! Be my wife! End my troubles!—and was staggered by his rashness, his weakness, and by the characteristic nature of such an outburst, for he saw how very neurotic and typical it was. We must be what we are. That is necessity. And what are we? Well, here he was trying to hold on to Ramona as he ran from her. And, thinking that he was binding her, he bound himself, and the culmination of this clever goofiness might be to entrap himself. Self-development, self-realization, happiness—these were the titles under which these lunacies occurred. Ah, poor fellow!—and Herzog momentarily joined the objective world in looking down on himself. He too could smile on Herzog and despise him. But there still remained the fact. I am Herzog. I have to be that man. There is no one else to do it. After smiling, he must return to his own Self and see the thing through. But there was a brainstorm for you—the third Mrs. Herzog! This was what infantile fixations did to you, early traumata, which a man could not molt and leave on the bushes like a cicada. No true individual has existed yet, able to live, able to die. Only diseased, tragic, or dismal and ludicrous fools who sometimes hoped to achieve some kind of ideal by fiat, by their great desire for it. But usually by bullying all of mankind into believing him.

The Tales of the Late Ivan Petrovich Belkin, Vladimir Pushkin

I read this collection of short stories packaged with Pushkin’s novella The Queen of Spades. I wrote about this latter as a Gambling Story, but have thought for a while about writing a companion piece about Dueling Stories (which I also love for their invocations of fate). Here’s one account, from the first story in the collection, “The Shot,” in which the narrator is infuriated by his cherry-eating adversary:

It was at dawn. I stood at the appointed place with my three seconds. With indescribable impatience, I awaited my opponent. The spring sun rose, and its heat could already be felt. I saw him in the distance. He was coming on foot, his jacket hung on his sword, accompanied by one second. We went to meet him. He approached, holding his cap, which was full of cherries. The seconds measured out twelve paces for us. I was supposed to shoot first: but my spiteful agitation was so strong that I could not count on the steadiness of my hand, and, to give myself time to cool off, I offered him the first shot. My opponent did not accept. We decided to draw lots: the first number went to him, the eternal favorite of fortune. He aimed and shot a hole in my cap. It was my turn. His life was finally in my hands; I looked at him greedily, trying to catch at least a trace of uneasiness. He stood facing my pistol, picking ripe cherries from his cap and spitting out the stones, which landed at my feet. His indifference infuriated me. What’s the use of taking his life, I thought, if he doesn’t value it at all? A malicious thought flashed through my mind. I lowered the pistol.

London Fields, Martin Amis

Probably the most entertaining novel I read this year, the phrase “insincere dart” from London Fields crosses my mind more often than its content would indicate. The narrator is taking a darts lesson from the colorful, darts-obsessed, petty criminal Keith Talent:

When I entered the garage for my first darts lesson Keith turned suddenly and gripped my shoulders and stared me in the eye as he spoke. Some kind of darts huddle. 'I've forgotten more than you'll ever know about darts,' says this darting poet and dreamer. 'I'm giving to you some of my darts knowledge.' And I'm giving him fifty pounds an hour. 'Respect that, Sam. Respect it.'

Our noses were still almost touching as Keith talked of such things as the address of the board and gracing the oché and the sincerity of the dart. Oh yes, and clinicism. He then went on to tell me everything he knew about the game. It took fifteen seconds.

There's nothing to know. Ah, were I the kind of writer that went about improving on unkempt reality, I might have come up with something a little more complicated. But darts it is. Darts. Darts . . . Darts. In the modern game, or 'discipline', you start at 501 and score your way down. You must 'finish', exactly, on a double: the outer band. The bullseye scores fifty and counts as a double, too, for some reason. The outer bull scores twenty-five, for some other reason. And that's it.In an atmosphere of tingling solemnity I approached the oché, or throwing line, 7ft 9 1/4 ins from the board, “as decided”, glossed Keith, “by the World Darts Federation”. Weight on front foot; head still; nice follow through. “You're looking at that treble 2.0,” whispered Keith direly. 'Nothing else exists. Nothing.'

My first dart hit the double 3. “Insincere dart,” said Keith. My second missed the board altogether, smacking into the wall cabinet. “No clinicism,” said Keith. My third I never threw: on the backswing the plastic flight jabbed me in the eye. After I'd recovered from that, my scores went 11, 2, 9; 4, 17, outer bullseye (25!); 7, 13, 5. Around now Keith stopped talking about the sincerity of the dart and started saying “Throw it right for Christ's sake” and “Get the fucking thing in there.” On and on it went. Keith grew silent, grieving, priestly. At one point, having thrown two darts into the bare wall, I dropped the third and reeled backward from the oché, saying — most recklessly — that darts was a dumb game and I didn't care anyway. Keith calmly pocketed his darts, stepped forward, and slammed me against a heap of packing cases. Our noses were almost touching again. “You don't never show no disrespect for the darts, okay?” he said. “You don't never show no disrespect for the darts . . . You don't never show no disrespect for the darts.”

Near To the Wild Heart, Clarice Lispector (translation by Alison Entrekin)

Every single one of my past roundups of passages has included something by Clarice Lispector, and this year is no exception. From her debut novel, which she wrote in her early twenties:

She remembered when she’d gone to fetch — what was it? ah, Civil Law — on the bookshelf at the top of the stairs, such an unprompted memory, so free, imagined even. . . How new she was then. Clear water running inside and out. She missed the feeling, needed to feel again. She glanced anxiously from one side to the other, looking for something. But everything there was as it had been for a long time. Old. I’m going to leave him, was her first thought, unprecedented. She opened her eyes, keeping tabs on herself. She knew this thought could have consequences. At least in the past, when her resolutions didn’t require big facts, just a small idea, an insignificant vision, in order to be born. I’m going to leave him, she repeated and this time the thought gave off tiny filaments binding it to her. From here on in it was inside her and the filaments would grow thicker and thicker until they formed roots.

How many more times would she propose it to herself, before she actually left him?She grew tired in advance of the small struggles she was yet to have, rebelling and then giving in, until the end. She had a quick, impatient internal movement that was only reflected in an imperceptible lifting of her hand. Otàvio glanced at her for a second and continued writing like a sleepwalker. How sensitive he was, she thought in an interval. She kept going: why put it off? Yes, why put it off? ahe asked herself. And her question was solid, demanding a serious answer. She straightened up in her chair, adopted a ceremonious position, as if to hear what she had to say.

Sentimental Education, Gustav Flaubert:

The aimless Frédéric Moureau, the protagonist of Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, was described by Flaubert as a fruit sec (literally, a dry fruit) — an idiom in French for someone who fails to excel in school. That tells us something about the nature of Frédéric’s progress in Sentimental Education. Flaubert described the novel as a “moral history of a generation” and it’s a cynical one; his protagonist flits from pursuit to pursuit, never quite committing himself to anything in particular. The one throughline of his education is Madame Arnoux, a beautiful woman he encounters as a young man and idealizes, unrequited, throughout the novel. Near the end, after a long absence, Madame Arnoux comes to see Frédéric and when she takes off her bonnet he discovers, with disappointment, that her hair has turned white.

She stayed there, leaning back, her lips parted and her eyes raised. Suddenly she pushed him back, despairingly, and when he begged her to say something, she lowered her head and said, “I would have liked to make you happy.”

Frédéric began to suspect that Madame Arnoux had come to give herself to him; and he experienced a surge of lust more powerful than ever, a furious, enraged desire. But at the same time, he felt something he could not express, a kind of repulsion, something like a terror of incest. And then another fear rose up, that of feeling disgust after the act. Besides, what a predicament it would create!—and suddenly, out of both prudence and a wish to not degrade his ideal, he turned away and lit a cigarette.

She looked at him, marveling.

“Such tact, such sensitivity! Only you! There’s no one like you.”

The first time I read Flaubert his prose struck me as nice, but this reminder of the strength of his writing has given me second thoughts.

Clarice Lispector, and her translator, Alison Entrekin, wow. Curious, has Entrekin translated more of Lispector's work?

Good stuff. You could probably quote most of "Herzog," it's really a virtuoso performance all the way through. And I have fond memories of going through Pushkin's Belkin Tales as an undergraduate Slavicist.