There's a mini-genre of 19th-century fiction I particularly enjoy: gambling narratives. Today, stories about gambling seem to come in two main flavors. The first is narratives of addiction: lives captured and shredded through the dopamine trap of intermittent reinforcement and exploitative business models. The second is narratives of systems: people who find edges or loopholes in an imperfect set of rules to bend chance in their favor (like this story of a man who learns to beat roulette). These narratives are thoroughly secularized, rational, and scientific.

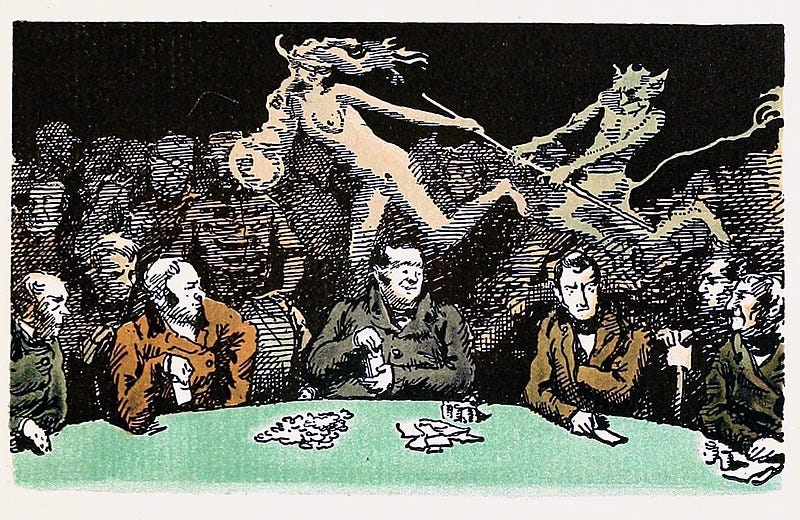

The gambling stories from the 19th century call on more mysterious forces: the cruelties of fate and fortune, honor and revenge, hubris and punishment. Through the medium of cards divine forces flow, and Mephistopheles enters the lives of ordinary people.

The typical protagonist of a gambling story is a young and unattached man of promise, often in the military. He is someone of modest means who hopes to climb in the world, constantly torn between discipline and impulse. His morality bears both the strictures of a society that rewards patience and frowns on debt, and the demands of a masculine ideal that valorizes bravery and risk-taking. The protagonist of Schnitzler's Night Games (another favorite) is such a man: he’s moved to gamble at the request of a friend in need, then emboldened by early wins, and within twenty-four hours finally driven to suicide from shame.

Hermann, the protagonist of Pushkin's short story The Queen of Spades (which you can find online here), is a bit of a different creature. The storytelling makes no effort to make Hermann sympathetic — there's no dying relative or friend in distress, nor any indication of what he wants to do with his winnings. He is driven only by obsession. His sole desire is to turn the forces of money — both a replacement for and an expression of divine fate — to his will.

His game of choice is faro, a card game once popular in France with relatively simple rules. The betting table is set up by laying out all members of a single suit of cards (these are extras) in a row, where players can place their bets. In each round, the players, or “punters,” place their chips on the card number they think will win. Then the game’s “banker” draws two cards: one banker’s card, the losing number, and one “player’s card.” Any bet placed on a number matching the player’s card wins, and anything matching the banker’s card loses. The other bets remain in play in the next round (there are a few extra modifications. This YouTube video helps explain how faro is played). According to Wikipedia, it was a more player-friendly game than most games of chance, easy to learn and with better odds than most games of chance.

When the reader first meets Hermann, an engineer in the military, he's sitting at the card table, watching the players closely without participating himself. He's fascinated by the game but refuses to play, citing his reason: “I am not in a position to sacrifice the necessary in hopes of acquiring the superfluous.”

At the table, he hears a story from one of the men about his grandmother, a countess and formerly a famous beauty. In her youth, according to the story, she once ran up significant gambling debts that her husband refused to pay off, and in desperation sought out help from a renowned gambler: the legendary comte de Saint Germain (who was a real person, though likely not a real count). He kindly (and perhaps in return for unspecified favors) shared his secret knowledge with her: a sequence of three cards that, if bet in order, would guarantee a win. The following day, after three correct bets in a row, the countess won back everything she needed to pay her debt and later was able to help out another aristocrat in distress by passing the secret to him. Hermann is fascinated by the story:

The story of the three cards had a strong effect on his imagination and did not leave his mind the whole night. ‘What if,’ he thought the next evening, roaming about Petersburg, ‘what if the old countess should reveal her secret to me! Or tell me the names of those three sure cards! Why not try my luck? … Get introduced to her, curry favor with her — maybe become her lover — but all that takes time — and she’s eighty-seven years old — she could die in a week — in two days! … And the story itself… Can you trust it?… No! Calculation, moderation, and diligence: those are my three sure cards, there’s what will triple, even septuple my capital, and provide me with peace and independence!

Of course, in a game of chance like faro, there is no sequence of three cards that can guarantee a win every time. So there is something supernatural about this secret, some special power that comes along with this knowledge. And the power is discharged upon use, its magic working only once: one of the stipulations of the secret is that anyone making use of it must never gamble again.

Hermann becomes obsessed with the idea of learning this sequence of three cards and devises a plan to force the countess to reveal them. To this end, he aggressively pursues the countess's meek and sheltered young ward, Liza, with love letters declaring his passion. His first letter to her is copied verbatim from a German novel, the contents of which Liza is unlikely to recognize because, like Mr. Casaubon, she can't read German. Liza, at first frightened and confused by his attention but with a romantic nature nurtured by novels, is eventually overwhelmed. She instructs him on how to gain entry to the house she shares with the countess, so they can rendezvous in person. She tells him to pass through the countess’s room, where there are two doors side by side: the left leading to Liza’s bedroom, and the right leading to a study where he can hide and wait. He chooses the latter.

I encountered the story of The Queen of Spades for the first time in the form of Tchaikovsky's operatic adaptation of the same title. The opera (in true operatic form) makes much more out of the romance between Liza and Hermann than Pushkin’s story does. The text and the music suggest that Hermann might truly love Liza and that when he chooses the study door over the bedroom door it represents the victory of his dark obsession over his chance at true love. Pushkin’s version is much colder: Liza is only an instrument for Hermann, his key to the house of the countess. He feels only brief, faint flickers of remorse at having exploited her.

If I were to do a little undergrad-level analysis, I might suggest that the story illustrates the transition point between an aristocratic society and a professionalized, capitalist one. Hermann is a striver, an engineer who hopes to rise through merit and is (mostly) rational in his approach to life — an avatar of the future. The countess has all the faults of her age and class: she's capricious, demanding, inconsiderate to her servants, and old-fashioned in her dress. Still, because of her past and her title, myth and romance cling to her. The room where Hermann confronts her is dominated by a portrait depicting her in all her former power and beauty — but it’s in this room where she discards the trappings of wealth, and becomes vulnerable and weak.

The countess started to undress before the mirror. They unpinned her bonnet, decorated with roses; took the powdered wig from her gray and close-cropped head. Pins poured down like rain around her. The yellow gown embroidered with silver fell at her swollen feet. Hermann witnessed the repulsive mysteries of her toilette; finally, the countess was left in a bed jacket and nightcap; in this attire, more suitable to her old age, she seemed less horrible and ugly.

Even with her glamour diminished, she still belongs to an exclusive club — holders of the secret knowledge — that Hermann cannot hope to enter except by force. In the end, each is responsible for the other's destruction. On my first read of the story, I understood it as a straightforward punishment of Hermann for the sins of hubris and avarice. But it's a punishment for the countess too: in her youth, she is rescued by the magic sequence, then later pays for it with her life.

In Romantic-era gambling stories, money is the life force of the universe — but rather than hoarded by nobles or accumulated by capitalists, it is distributed by chance, or fate: giving sinners a reprieve or striking down the proud, like an old pagan god.

That's quite a turn from Jane Austen, where money was also a driving force. Old money was viewed as destiny. Do you think that the industrial Age and the new money it brought changed that? Did the rise of machinery increase popular interest in supernatural stories, chance, gambling?