First, a quick recap. I spent the last two weeks of September in Italy, on a solo vacation. The first week I spent in Civitella d’Agliano, a small town near the Lazio-Umbria border, and my intention was to write, read books, and eat — happily, I enjoyed all three. The second week I visited Florence (three nights) and Rome (three nights), and my intention was to eat and look at paintings. Again, I did both in abundance.

Practicalities, for the curious

A note on the practicalities for those who may be considering travel: COVID-19 tests are necessary to both enter Italy and return to the USA. I’d heard that it can be tricky for a tourist to get a test in Rome during the crucial 72-hour window, so before flying I purchased a BinaxNOW kit, which you can take with you and then use to self-test while an observer watches over video and ratifies your results. All of that went very smoothly.

Inside the country: you need to show proof of vaccination to do anything interesting (most saliently for me, to eat inside a restaurant or enter a museum). It wasn’t a problem that I didn’t have an EU Green Pass with a QR code to scan; I showed my white paper CDC card and that was fine everywhere. Shops and restaurants were open and bustling, everyone wore masks. I did not get COVID-19, did not get my wallet stolen, did not get hassled by scammers, did not get ripped off by any taxi drivers. Some tourist attractions were very crowded; others were eerily empty. The other tourists were mostly European, but there were a few Americans around, and a sprinkling of Brits and Aussies. The first American voice I heard in Italy, a man behind me in line at the Accademia in Florence, spake this American sentence to his girlfriend: babe, can I get you a coke zero?

The Yellow Wall

While in Civitella d’Agliano I read my annual volume of In Search of Lost Time. This one was the fifth, The Prisoner, which the book jacket describes as “a tragedy of possessive love” although I don’t think the words “tragedy” or “love” really apply to the possessive relationship in question.

I have a lot to say about The Prisoner, but it will need to wait for another time, because I want to focus on a particular passage that was often on my mind, for reasons that will become obvious, as I traversed the famous Italian galleries. I was struck very much after reading it, then looked it up to find that it is justly quite famous — though less famous than the bit about the madeleines, perhaps because it takes 5 volumes to get to it instead of [PGES].

We see the final day in the life of the fictional novelist Bergotte, celebrated in his prime but since fallen out of fashion. The narrator tells us that Bergotte has been ill, troubled by nightmares, mostly confined to his room. He’s enduring a series of unpleasant medical treatments, prescribed by a series of doctors with contradictory advice.

But then, something moves him to go out.

This is how he died: after a mild uremic attack he had been ordered to rest. But a critic having written that in Vermeer's View of Delft (lent by the museum at The Hague for an exhibition of Dutch painting), a painting he adored and thought he knew perfectly, a little patch of yellow wall (which he could not remember) was so well painted that it was, if one looked at it in isolation, like a precious work of Chinese art, of an entirely self-sufficient beauty, Bergotte ate a few potatoes and went out to the exhibition. As he climbed the first set of steps, his head began to spin. He passed several paintings and had an impression of the sterility and uselessness of such an artificial form, and how inferior it was to the outdoor breezes and sunlight of a palazzo in Venice, or even an ordinary house at the seaside. Finally he stood in front of the Vermeer, which he remembered as having been more brilliant, more different from everything else he knew, but in which, thanks to the critic's article, he now noticed for the first time little figures in blue, the pinkness of the sand, and finally the precious substance of the tiny area of wall. His head spun faster; he fixed his gaze, as a child does on a yellow butterfly he wants to catch, on the precious little patch of wall. "That is how I should have written, he said to himself. My last books are too dry, I should have applied several layers of color, made my sentences precious in themselves, like that little patch of yellow wall." He knew how serious his dizziness was. In a heavenly scales he could see, weighing down one of the pans, his own life, while the other contained the little patch of wall so beautifully painted in yellow. He could feel that he had rashly given the first for the second. "I would really rather not, he thought, be the human interest item in this exhibition for the evening papers." He was repeating to himself, "Little patch of yellow wall with a canopy, little patch of yellow wall." While saying this he collapsed on to a circular sofa; then suddenly, he stopped thinking that his life was in danger and said to himself, "It's just indigestion; those potatoes were undercooked." He had a further stroke, rolled off the sofa on to the ground as all the visitors and guards came running up. He was dead.

What sets this apart from more sentimentalized encounters with beauty at the moment of death1 is its ambiguity, how Bergotte seems to regret sacrificing his life for that patch of yellow wall even while rapt with its artistry, and in the end attributes his stroke to bad potatoes. But to even pose the glittering question — to measure a life’s work against a Vermeer, against a fragment of a Vermeer2 — and in the passage be simultaneously grateful for the rejuvenation, the beauty, the birth of a new way of looking, while suggesting that the same could kill you? If you’re the kind of person who’s going to read Proust in the first place, it’s powerful stuff.

After looking up the passage, I read that Proust actually suffered a bad dizzy spell while on an outing to view very same painting. He survived the encounter, but it was to be his last excursion. After returning home that day he remained in his cork-lined room for the rest of his life, and his revisions to this passage were some of the final lines he wrote before his death.

What moved me in Italy

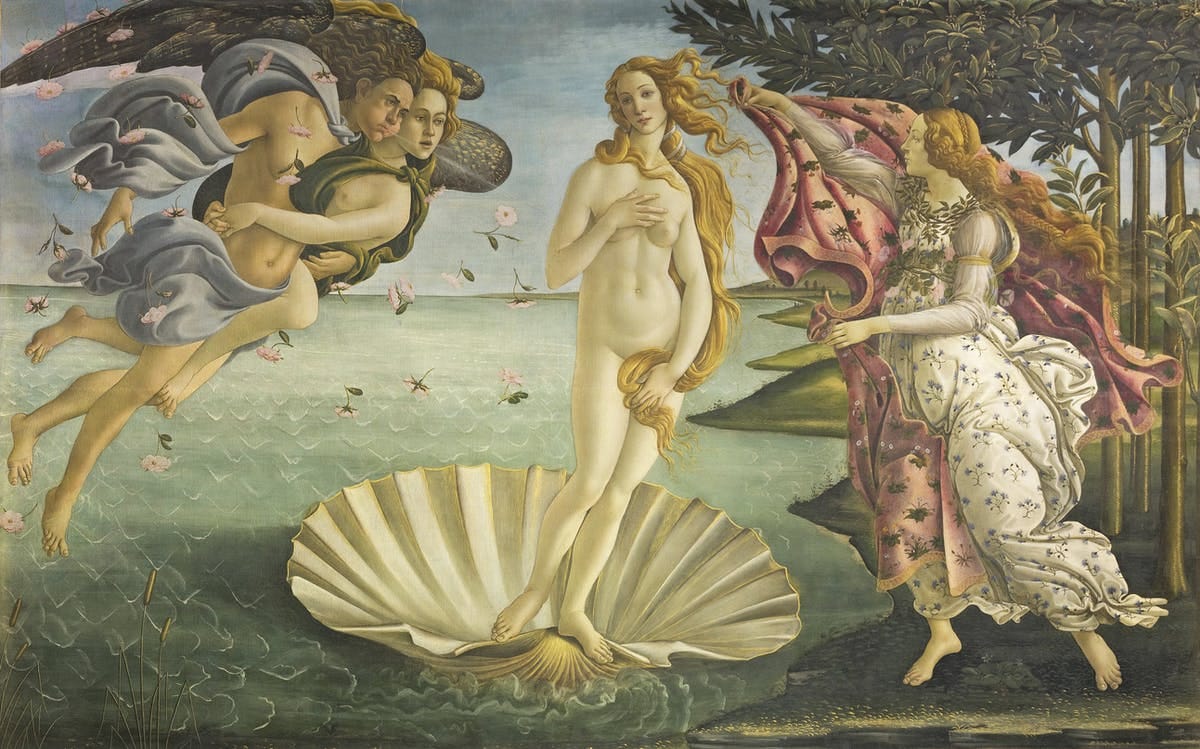

I was in no danger of dying from any of the artworks I saw in Italy, but I tried to be as alert as I could to all the small places where beauty might live. It can be hard to look at The Birth of Venus, for example, with fresh eyes, but I think it’s always worthwhile to try. I think even if we’re cerebral-minded, approaching something with scholarly or technical interest, most of us still hope that an encounter with art can make us feel something. Below are some of the artworks and places that made me feel something. Some (even most) of the things I list here will be over-familiar, but I always tried to see something new about them.

Botticelli, The Birth of Venus

Entering the Uffizi is a bit miserable right now (perhaps it is always). Even when you have a pre-reserved ticket you need to stand in an interminable line where everyone’s vax pass is checked, and once you’re past the gates you’re funneled through a number of dreary passages, up and down various flights of stairs, worn out before you lay eyes on a single work of art.

And then for a while, if you’re following the course, you go through rooms where most of the art consists of gilded stone-faced madonnas with frowning babies on their laps. They of course have their own austere, rough beauty, but then as you pass through the decades and centuries there’s a perceptible opening of the windows, a breath of air. You start to see movement, lightness, even sensuality. And then, because of the crowds, you can sense that you’re in front of it. And it’s beautiful.

I had never before seen this painting in the flesh (varnish), and my mental image of it included the shell, the hair, the puff of wind. But seeing it there, I found I had never before noticed the pink blossoms floating carelessly through the air. And, in front of it, I felt the temporality of it — how we are observers witnessing this brief moment of her nakedness before the attendant throws the cloak around her, before she wraps it around her and steps off the shell and onto the grass. In this way it does look like a birth, an instant when something new and defenseless has entered the world, something just about to change and transform.

Michelangelo, the “Bandini” Pietà

The famous Pietà is the one in Rome, and this was a work that Michelangelo considered a failure, abandoning the sculpture partially completed and even attempting to destroy it. But a major restoration of the sculpture was just completed, and I felt very lucky to have seen it in its new state.

The image here does not show clearly what I remember the most — the attitude and expression of Mary, taking hold of her son. She is not yet holding him up, he is still in motion, fragile, unsupported. In her face I saw something almost like release, almost as though it is a relief to feel the presence of his body as it collapses into her arms.

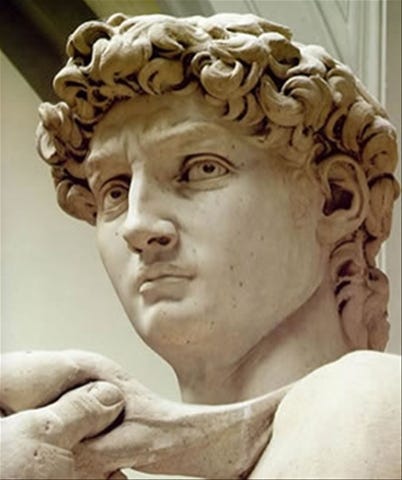

David

I’ll be brief here. What I didn’t expect before visiting David in person is how frightened his face actually looks.

Andrea Pisano

I was, unexpectedly, completely charmed by these little tableaux by sculptor Andrea Pisano depicting the various arts and sciences. They’re in the Museo dell'opera del duomo in Florence.

Sculpture:

Animal husbandry:

Building:

Wine-drinking:

Rossini

The opera composer Rossini’s tomb can be found in the Basilica de Santa Croce in Florence. After enormous early fame, he retired relatively young from composing3 and spent most of his later life in Paris, hosting salons, cooking enormous rich meals for himself, and being a wit and overall bon vivant. He was buried there at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, but two decades later he was exhumed and moved to Florence.

For context: the Basilica de Santa Croce is the site of a number of important tombs and memorials, including for such giants as Michelangelo, Galileo, and Machiavelli. There are also memorials to Dante and Leonardo da Vinci, though their bodies aren’t interred there.

Something about the presence of Rossini among these figures was funny and oddly touching to me. A man who was famous mostly for light opera, laziness, and quips about Wagner, and who by all accounts took life lightly, mattered enough to Italy to haul his body here two decades after his death and build an elaborate monument to him alongside Galileo and Dante.

He wrote a dedication for his final work, a sacred Mass, and it reads like this:

Dear God, well, here it is, finished at last, my Little Solemn Mass. Have I really written sacred music, or is it just more of my usual damn stuff? I was born for opera buffa, as You well know. Not much skill there, just a bit of feeling, that’s the long and the short of it. So, Glory be to God, and please grant me Paradise.

Perhaps there were strange politics afoot, but I’ll call this tomb an indication that his wish was granted.

Penitent Magdalene, Caravaggio

This painting hangs in a strange and lavish gallery occupying part of the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, which is still owned by the aristocratic Doria Pamphili family. It’s both a strange, and not-so-strange, place to look at great paintings. I visited the gallery near the end of the day and the rooms were almost entirely empty, adding to the feeling of strangeness and desolation. The setting is a series of heavily ornamented rococo rooms, and the paintings are all hung in the old-fashioned way, the manner of private collections, with works stacked on top of each other from eye level up to the ceiling. The lighting and positioning makes the paintings hard to examine, and many of them look like they need cleaning. They’re (mostly) labeled with the names of their painters, but not dated; there are almost no printed explanatory materials; but there are paintings from many great artists, including Raphael, Titian, Velasquez, Breugel, and three paintings by Caravaggio (although one of these is disputed).

This painting depicts a regretful Mary Magdalene, but on first glance you’d never place it as a biblical painting. She looks very much like an ordinary girl in trouble. My first thought, an impression that remains, was that she looks like someone who might be unexpectedly and unhappily pregnant, and regretting the affair that led her there. Her hair is disheveled and undone, but not in the artful Botticelli way, more like the it’s three in the morning and I couldn’t sleep way. There’s no indication of the time of day, but to me it looks like three in the morning. You can’t see it in this image, but there’s a tear on her cheek. Not an ounce of melodrama. This is perhaps the most realistic depiction of private shame that I’ve seen.

The Sistine Chapel, and Jethro’s Daughter

Again, here I’ll be brief. The beauty and vibrancy of the ceiling and The Last Judgement are almost overwhelming. But this time I had something else to look for, thanks to Proust.

In a famous early scene in Swann’s Way, the titular Swann is contemplating a woman with whom he’s having a flirtation. He isn’t especially interested in her — she’s not his typical physical type and he at first doesn’t find her attractive. But one day he’s looking at reproductions of the Sistine Chapel frescoes and notices a resemblence to this woman, painted by Botticelli, in one of the frescoes depicting the life of Moses:

If she has the kind of face that would have interested Botticelli, he decides, then she’s beautiful enough for him.

Keats’s Room

On my last day in Rome I visited the Keats-Shelley house, a small museum in a building next to the Spanish Steps, notable for being the place where the poet John Keats died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty-five.

I have read and enjoyed some of Keats’s most famous poems, but would have never described myself as a fan. I don’t own any of his books or collected works. So I was unprepared for the strong emotional reaction I felt on entering the room where he died.

It’s such a small room, and narrow, hardly enough room to stand up next to a single bed. There’s a fireplace, where his friend Severn sometimes cooked food for him. On the ceiling there’s a pattern of painted flowers — painted rather shoddily (the museum claims that they are from his time). Looking up, I imagined Keats lying in the bed all those weeks, staring at the beams and the pattern of flowers, growing maddeningly familiar with every rough-edged petal.

My cynicism tells me that Keats’s story is a classic tearjerker, practically engineered to arouse emotion. His great vivid talent, his beloved Fanny Brawne left behind, his young brother dead in his arms from the same disease a few years before, his resulting foreknowledge of exactly what was going to happen to him. Knowing he’d never see spring again. Hearing life happening out the windows, staring at the daisies on the ceiling.

The smallness of the room, the windows out on the busy piazza, the sad ceiling daisies, the fireplace. I felt the presence of death here. It takes no great sensitivity to be moved by it. But I know I’ll never forget it.

Horribly, I’m remembering the scene in The Last Samurai, the Hollywood movie starring Tom Cruise, where an actual Samurai character, mortally wounded, contemplates the cherry blossoms, saying “they are all perfect” before expiring.

Here’s a link to The View from Delft, but be aware — it’s very much not obvious which “patch of yellow wall” Bergotte was looking at, or even if such a patch exists. This piece poses a few possibilities, while this wonderful Peter Schjeldahl essay suggests that there’s no such patch at all, and what Proust is doing is recording an impression, a memory of the painting that may not correspond to precise details.

There are a lot of theories why, but I think the most compelling is that he just didn’t feel like composing anymore and wanted to enjoy his life.