The Prisoner, the fifth volume of In Search of Lost Time, represents a great narrowing. It’s the shortest in the series thus far — a slender 400 pages — and, as its title suggests, the most confined. The better part of the story takes place inside the narrator’s Paris apartment, where he likes to lie in bed and listen to the sounds of the street just outside. The narrator finally gives himself a name: Marcel, to no one’s surprise.

(note: I read the Carol Clark translation from Penguin Classics)

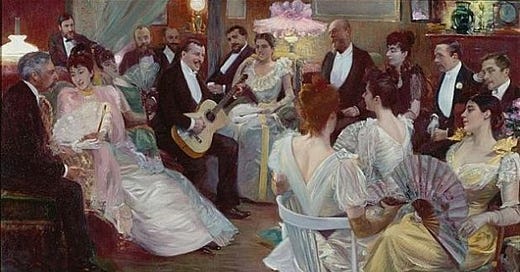

Characteristically, it begins in solitude and reaches its climax at a party, at a musical evening hosted by the tireless salonnière Madame Verdurin. But while the previous volumes chronicled an opening of the world, an initiation to the pleasures of adult life, this volume’s overwhelming feeling is one of hopelessness, retreat, and decline.

Thus far, I hadn’t been thinking of Marcel (as I now may refer to him) as an unreliable narrator, so scrupulous he is of noting every observation, every emotion, every mistake and misconception and remembered conversation. But most pronounced in this novel are the things occluding his vision, the elements of human life he has no access to.

The prisoner of the title is a woman, Albertine, his adolescent crush and now his loyal girlfriend (heavy irony on the loyal). Fearful that she will be unfaithful to him — he is obsessed with the idea that she enjoys sexual trysts with other women, and conceals them from him — he monitors all her movements, prevents her from going out alone, and pays his chauffeur to keep tabs on her.

To Marcel’s surprise and sometimes consternation, Albertine is entirely compliant. When she hints that she might visit some of her friends one afternoon, he moves to thwart her plans, heavily suggesting she go instead to the theatre. But then, imagining a possible transgression at the theatre, he summons her back to him in the middle of the performance — and she returns without complaint. In his apartment, she stays quietly in her room until he calls for her, then remains with him until he dismisses her. Due to his worsening health, she is forbidden even from opening the window.

He marvels at the power he holds over her:

Her cage was so secure that some evenings I did not even call for her to come from her room to mine, she, the former leader of every party, whom I could never catch as she flew past on her bicycle and whom even the liftboy could not bring back to me, leaving me with no hope that she would come, yet still ready to wait for her all night. Albertine in front of the hotel — was she not the leading actress of the fiery beach, stirring up jealousies as she advanced on that natural stage, speaking to no one, disdaining the regular audience, dominating her friends; and this actress, so lusted-after, was she not now (removed from the stage by me, enclosed in my quarters) safe from all those whose desires would seek her in vain, as she sat, sometimes in my bedroom and sometimes in her own, drawing or doing some small piece of carving.

Once in a museum I saw a collection of miniature ships, carved entirely by prisoners from the chicken bones in their rations. That he describes Albertine as occupying herself with carving is, I think, no coincidence.

Marcel lingers on the ironies and contradictions of his possessiveness. They are many, each named and fully elucidated. The more he controls her, the less he can be certain of her real feelings; the more he confines her, the less love he himself feels for her. He hears double meanings in everything she tells him, and the more she tells him about her past, the more dalliances he imagines. He knows that the more he presses her, the more she will resort to lies; if she reassures him, he trusts her even less. He himself lies to her constantly, trying to catch her out; he tells her the opposite of his true feelings and assumes she is doing the same. When he is in her company, he longs for solitude; when he is away from her, he’s consumed with suspicion. He desires desperately to possess her, but knows that if he succeeds he will no longer love her. And in constraining her life he also constrains his own. He longs to go to Venice, but his suspicions mean that he can neither travel there with her nor go without her. He is reluctant even to take her to an art gallery, fearing she will be aroused by the nudes. Sometimes he fantasizes that she’ll escape on her own, breaking away and saving them both, but still he does all he can to prevent it.

The reader spends so much time with his paranoid attempts to untangle the threads of what Albertine tells him that I found it dizzying, after several hundred pages, to find that we are no closer to the truth about her than at the beginning of the book. Has she been unfaithful to him, even once? Does she even desire women at all?

To what extent the reader should imagine her as a woman seems to be a matter of scholarly debate, given Proust’s homosexuality and some oddities in the way he describes her imagined behavior, which seems more stereotypically characteristic of gay men. The most “feminine” thing about her may be the way he sees her: as his prized possession, his caged bird, both a whore and a virgin, whose thoughts he obsesses over while caring almost nothing for her happiness, or even her inner life. Despite all his interrogating, he does not learn a single thing about her. He can only truly enjoy her presence when she is asleep: “There are some faces which take on an unaccustomed beauty and majesty the moment they no longer have a gaze.”

The inner flap copy describes The Prisoner as a “tragedy of possessive love”, but it looks nothing like love as I understand it, and it seems more and more like Marcel — the keenest observer of social dynamics, the vivisector of every utterance and emotion — is a stranger to one of the profoundest aspects of the human experience: that of truly caring for another, to see their happiness as intertwined with one’s own. Even his friendships have a transactional aspect to them. His view of romantic love is perhaps the most cynical of any of the great novelists I’ve encountered:

Unkindness and deviousness in love are so natural! If the interest we take in other people does not prevent us from being gentle with them and helpful to them in their wishes, then that interest is feigned. Other people are a matter of indifference to us, and indifference does not prompt us to cruelty.

A few pages later, he scoffs at the idea of trust between lovers, “as if it were not natural to mistrust those who love us, the only people who have an interest in lying to us, whether to find things out or to stop us doing what we want.” Love, for him, is inseparable from the desire to possess and control — and can be sustained only as long as the desire remains unfulfilled.

When Marcel emerges from his apartment and starts to think of society, of friends, he describes a world of decline. Figures of towering importance in the first novels of the series, like Swann and Bergotte (who I wrote about last time), are weakening, sickening, dying.

In particular we see the downfall of the formidable Baron Charlus. Marcel has previously held Charlus up as the pinnacle of erudition, taste, intelligence, aristocratic refinement as well as social cunning, always knowing exactly how to maintain his position, punish his enemies, procure lovers, and humiliate upstarts. But in this volume we see him aging, sloppy, ridiculous. He’s a little reminiscent of Aschenbach at the end of Death in Venice: wearing too much makeup, speaking and acting recklessly, drunk with infatuation for a younger man, seemingly oblivious to how close he is to ruin and death.

Another character describes him as one might a museum curiosity:

“If you think your wife or your daughter might be interested, may I say that the Baron de Charlus, the Prince of Agrigentum, the descendent of the Condés, will be at my lecture. It’s something for a child to remember, that she saw one of the last truly characteristic descendants of our aristocracy … he will be the only other person on the platform, a stout, white-haired man with a black mustache, wearing the Military Medal.”

The Prisoner is perhaps the easiest volume of the series so far to read, but for me was the most difficult to love. The bleakest aspects of the Proustian worldview — that love always destroys itself, that anticipation and memory are more satisfying than experience, that social life is a series of lies and power games, that the majority of our desires are self-frustrating — are here in all their velvet barrenness. He finds redemption only in art and creativity, precisely because it lives in the realm of memory, desire, sensation and idealization, a product of the mind rather than the world, something outside of time. Edith Wharton, who was deeply impressed by Swann’s Way but put off by reports of Proust’s extreme snobbery, had this to say about him: “His greatness lay in his art, his incredible littleness in the quality of his social admirations.” Both the greatness and littleness can be found in this prison of a book, in dazzling quantities.