As I mentioned last week, I completed the final volume of In Search of Lost Time while waiting on the tarmac of the Charles de Gaulle airport. It felt appropriate to be finishing it (technically) in Paris. About halfway through reading Swann’s Way for the first time back in 2017, I realized that I would inevitably read all seven books. I feel similarly certain that at various points in my life I will reread them, perhaps in a different translation (and perhaps doing some judicious skipping). Even though at times they bored or confused me, each volume gave me an enormous amount of pleasure, making me want to share and reread all the best parts. A few intelligent and creative friends have told me that they tried to read Proust and found him intolerable, and I’ve heard about various other erudite people who feel the same. No one has ever told me that they tried Proust and loved him. So whenever I write about his books in this newsletter, I feel I need to apologize: I’m sorry, I don’t know why I’m like this.

Of course, he’s hardly obscure and neglected. A New Yorker piece by Adam Gopnik from 2021 notes that the secondary literature about Proust is voluminous to the point of being overworked1:

Why some writers get this kind of attention—rooted in encompassing appetite rather than in mere admiration—and some do not is hard to know and interesting to contemplate. Chekhov, born a decade earlier, is a writer of similar stature, and his plays are genuinely popular. But only specialists debate his translators, and there are no books delving into the originals of his characters, or providing recipes for Chekhovian blini, or explaining how Chekhov can change your life, or presenting photographs of his intimates. Proust, by contrast, is a sort of improbable Belle Époque Tolkien, the maker of a world with passports and maps and secret codes, to which many seek entry.

He continues by illustrating how Proust’s subject matter, described baldly, seems to be ludicrously trivial:

He is, after all, the writer who put the long in “longueur”—whose subject is not war and peace, or the making and breaking of a dynasty, or, as with Joyce, the history of literature implanted in an urban day. His terrain is, rather, the strangled loves and pains of a small, fashionable circle, with much of the novel spent with the narrator going back and forth to beach resorts and feeling things, and many more pages, particularly in the middle books, where he simply takes trains, feels jealous, then feels less jealous, then more.

Proust’s grand themes largely concern interiority and sensation, which don’t lend themselves well to plot, or to any of the traditional tension-creating devices found in books like Save the Cat. But I will say that if you find Proust to be your thing, every volume is like unearthing treasure, or having a conversation with an interesting friend. At various points I’ve considered compiling a “lazy reader’s guide to Proust”, noting which scenes are the most revelatory and which can be safely skipped. My advice for giving it a try would be not to start on page one of Swann’s Way — I found the Combray sections, as a whole, a bit of a slog — but to skip ahead to the middle section of the book, “Swann in Love”, which can be read as a standalone novel and features most of his pleasures while minimizing the longeurs. And, unlike reading Tolstoy (say), even though all the aristocratic characters have about five different names, it’s not really very important to keep track of who they are. They float in and out of parties, fashionably or unfashionably. Even Marcel couldn’t keep track of them, half the time.

Now, on to the final volume.

I found The Fugitive (volume six, which I read last year) to be the weakest and slightest of all I had read thus far, so my hopes for the final volume — translated in this edition as Finding Time Again, which sounds a bit too self-helpy for my taste — were not high. But I was wrong: it contains some of his best and most moving sequences, with the entire second half a tour de force.

The narrator begins the book in a state of aimlessness, having just spent several years in a Magic Mountain-style sanitorium. The woman he once loved is dead, and what’s worse, he no longer has any feeling for her. World War I is raging, and his natural habitats — fashionable salons, seaside resorts — are lost or irrevocably changed. The fashions are all different and not to his taste. His friends are dying, or becoming ridiculous in old age, and his own health is beginning to fail. Most importantly, his one desire in life, to become a writer, seems unattainable.

He reads an article by a celebrated writer about a few of his friends, and is thrown into despair. The friends in question are painted as influential tastemakers, while he (and the reader) has mostly known them as petty and vapid. The article includes a lot of “writerly” observations, small details about decor and dress, allusions to history, and flowery metaphors. If this is what literature is, he thinks, I’m not cut out for it:

Certainly I had never concealed from myself the fact that I did not know how to listen, nor, as soon as I was not alone, how to observe. My eyes would not notice what kind of pearl necklace an old woman might be wearing, and anything that might be said about it would not penetrate my ears. Yet I had known these individuals in daily life, I had often dined with them … to me they had all seemed insipid; I could recall the numberless vulgarities of which each of them was compounded…

Later, his seeming unsuitability for literature is confirmed on a train ride. He encounters a line of trees, illuminated beautifully by the sun, and finds himself completely unmoved:

If ever I could have thought of myself as a poet, I know now that I am not…If I truly had the soul of an artist, what pleasure should I not experience at the sight of this screen of trees lit by the setting sun, these little flowers on the embankment that reached up almost to the carriage step, whose petals I could count, and whose colors I was careful not to describe, as so many good men of letters would, for could one hope to transmit to the reader a pleasure one has not felt oneself?

But of course, since this is Proust, we know that he changes his mind. At the book’s midpoint, while walking across some uneven paving stones on his way to a party, a powerful sense-memory of his time in Venice floods him with feeling, and he has a flash of insight: that he won’t strive to create detailed, minutely observed treatments of grand themes (for which he has no talent), but rather of life as he experiences it internally — that is, filtered through memory, emotion, imagination, and sensation. In the subsequent pages, he lays out his plans for his magnum opus, articulating what it will require of him. It would be useless, he concludes, to travel to the scenes of his past, since he wants to write not about those places but instead his feelings and memories about them, which would be spoiled by an encounter with the facts. Instead, he will keep to his study, and devote the rest of his life to writing his book. He realizes, too, that all his past disappointments and suffering are a great gift to him, for his own life will be the source of all his material.

Putting these conclusions at the end of the series, rather than as an explainer at the beginning, is a masterstroke. Rather than didactic, they come as revelatory: the reader, having just finished the opus the narrator is planning, now understands the reason for the novel’s strange, wandering structure, its vagueness in some aspects and obsessiveness in others. Even the faults of consistency now seem to fit, since it’s the nature of memory to be imperfect. And what follows is a stream of advice for aspiring writers, all fascinating to me, outlining how to do what he has done. Some current writers of autofiction have doubtlessly taken it to heart.

The next scene, the party that finally closes off the story, is the Bal des têtes sequence, which I wrote about a couple of weeks ago. It’s easy to recap: the narrator, shortly after his fateful walk across the paving stones, arrives at his party. It’s full of old friends he hasn’t seen in a long time. He’s dismayed to find that they all seem to have put on costumes: their faces are deformed, their hair is white, their gait and manners are altered. He quickly realizes that what appears to be a disguise is in fact old age. It takes some time for the rest of the truth to sink in: he, himself, has also grown old, and is getting uncomfortably close to death.

The sequence is long and relentless, as he settles on each face and describes what has happened to it. Some are wearing makeup and dying their hair, men and women both, with varying success. A woman he remembers as a great beauty is now matronly; a friend who used to always have a ready quip now struggles for words. Not only that, but their social statuses have shifted, and as they progress toward irrelevance, they no longer possess the grandeur that formerly entranced the young Marcel.

It was painful for me to have to retrieve these [memories] for myself, for time, which changes individuals, does not modify the image we have of them. Nothing is sadder than this contrast between the way individuals change and the fixity of memory, when we understand that what we have kept so fresh in our memory no longer has any of that freshness in real life, and that we cannot find a way to come close, on the outside, to that which appears so beautiful within us, which arouses in us a desire, seemingly so personal, to see it again.

To tell the truth, as someone who recently enjoyed a milestone birthday, the Bal des têtes shook me up.

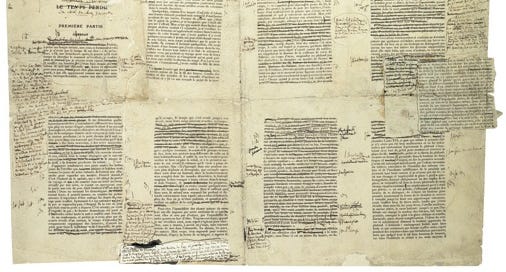

When he died, Proust left his magnum opus, in a real sense, unfinished. The later volumes, including this one, existed in draft form, but had not been fully revised. In particular, Finding Time Again existed only in a handwritten copy, with corrections written in the margins, and some material written on scraps of paper tucked between the pages or glued to the edges of them. As a result, different versions of the text exist, with its editors taking various approaches: either fix up the inconsistencies and repetitions, discarding some material and moving scenes around, or try to replicate the state of the draft as Proust left it. His earliest editors took the former approach, while later editions have preferred the latter.

This knowledge is particularly poignant when reading the book, as some of its greatest passages concern the urgency of the artist’s task in the face of approaching death:

The mind has its landscapes and only a short time is allowed for their contemplation. My life had been like a painter who climbs up a road overhanging a lake that is hidden from view by a screen of rocks and trees. Through a gap he glimpses it, he has it all there in front of him, he takes up his brushes. But the night is already falling when there is no more painting, and after which no day will break.

Other Amateur posts about Proust:

I’ll note that this essay makes the common mistake of placing the most famous scene, the tasting of the madeleine, at the beginning of the novel; in fact, it takes about 50 pages to get there.