Many stories attempt, as their project, to build sympathy for people who exchange the real world for a romantic fantasy — Don Quixote being the prototypical example, continuing with Emma Bovary, Norma Desmond, and innumerable dreamy protagonists of books written for children. Such people are often intolerable in real life, at least past a certain age, but if we take as given the elevating qualities of the imaginative spirit, they can seem noble and even revolutionary in fiction.

An observation that has been repeated to the point of cliché about the 1930’s is that amid the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe the most successful movies were about rich people: women in bias-cut satin dresses with pencil-thin eyebrows exchanging witticisms with tailcoated men with pencil-thin mustaches. The implication is that people crave escapism, not revenge, in difficult times. But this has always been an oversimplification. If you listen to “We’re In The Money,” which features in a scene from Bonnie and Clyde, the lyrics are mostly about poverty: having money means not having to stand on a breadline, and being able to face your landlord without shame.

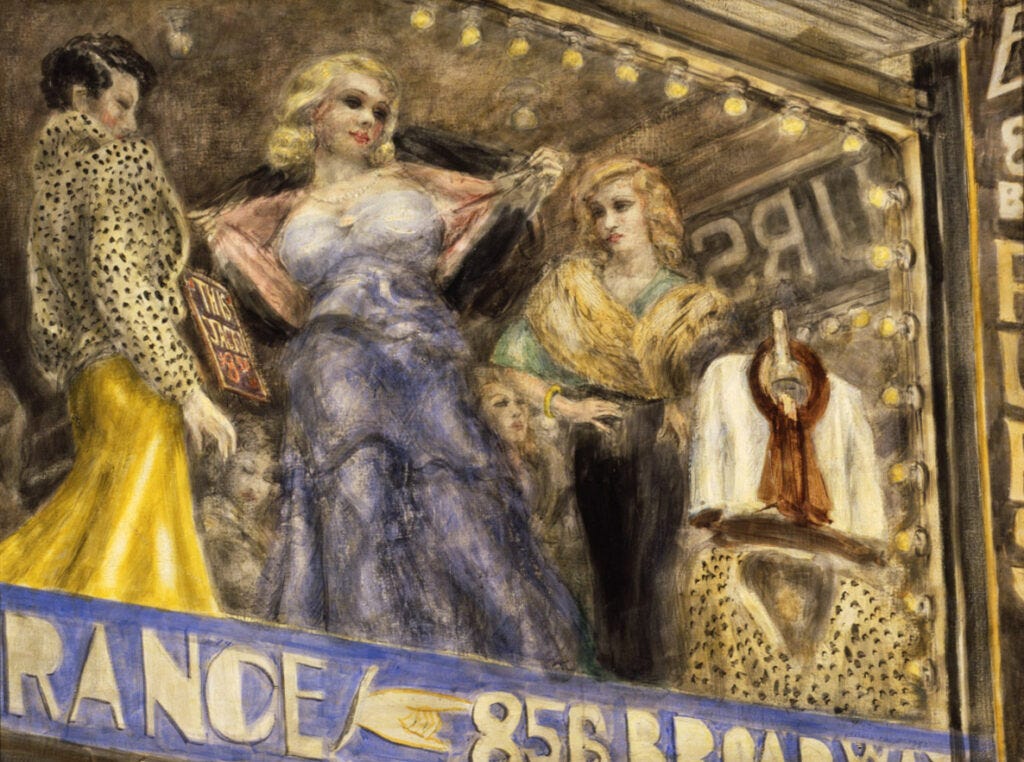

The 1981 movie Pennies from Heaven, a Hollywood adaptation of the British TV miniseries of the same name, takes this observation about the 1930’s as its premise. Set in the depression-era midwest, its antihero is a man named Arthur (played by Steve Martin), a failing traveling sheet music salesman who wants life to be “like it is in the songs,” using music to escape from the disappointing realities of his marriage (principally that his wife doesn’t enjoy sex with him). While on the road, he pursues and seduces a virginal schoolteacher named Eileen (Bernadette Peters), inventing a sob story about how his wife has died in a motorcycle accident. When she becomes pregnant, she loses her job and is forced to leave her home. Arthur evades responsibility, drains his wife’s savings to open a record store (which fails immediately), and becomes implicated in a murder he didn’t commit. In the city he reunites with Eileen, who out of desperation has turned to prostitution. The two try to run away together, but the police catch up to them. A false and ironic “happy ending” follows a scene of Steve Martin singing “Pennies from Heaven” directly to the camera while a noose hangs ominously in the background.

The primary couple is mirrored by two figures out of myth, or perhaps Russian literature: the “Accordion Man,” a destitute busker who plays hymns for passers-by (played in the movie by theater luminary Vernel Bagneris), and the Blind Girl, who walks home along the same road each day without fear of harm. They are harbingers of death, like the peasant woman near the train tracks who haunts Anna Karenina.

The BBC series was a modest hit, but the Hollywood version was a commercial disaster despite critical praise (including an enthusiastic review by Pauline Kael). Watching it, I could easily understand its failure in the United States. The adjectives listed next to its thumbnail on Amazon Video are “bleak” and “downbeat.” The musical numbers feature the characters lip-syncing over 30’s-era recordings of popular songs, to uncanny effect. And the Steve Martin character is unsympathetic and not at all comic — he’s belligerent and boorish with other men, shockingly cruel to his wife, and takes no accountability for ruining Eileen’s life. In the BBC series, the characters are clearly not professional dancers, singing and dancing a little awkwardly to the old songs the way an ordinary person might dance in their living room. But the Hollywood version features seasoned stage stars, impressive dance routines and glossy, high-budget production numbers, exaggerating the difference between “reality” and the fantasy of the musical numbers.

The cruelty of the BBC version, though its story is considerably more violent, is softened by its Britishness, its muted color palette, its modesty, and the shy awkwardness of its musical sequences. The Hollywood version, to me, carries its material with more style and grandeur, waving away any pretense to innocence or cuteness. As a fan of musicals generally, I was surprised never to have encountered it before — and surprised it hasn’t been a target, as far as I can tell, for rehabilitation as an under-appreciated classic.

Its most meme-able scene is a bawdy tap-dancing striptease performed by a young and nearly unrecognizable Christopher Walken as Eileen’s pimp:

Fred Astaire attended the movie’s premiere but hated the experience. “Every scene was cheap and vulgar. They don't realize that the '30s were a very innocent age,” he said. Of course, we’re always making a mistake if we think of the past as “innocent” simply because they faced different problems from ours. And the 1930’s, in particular, was not innocent but reactionary. One might argue that it’s us, in the 2020’s, who are too innocent of dangers that were all too familiar to them.

I went into Pennies from Heaven without any knowledge of the plot, and spent much of the running time wondering what kind of movie I was watching, whether I was supposed to find the characters sympathetic or not. But the argument of the movie crystallized when watching its version of “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” which begins by imitating the classic Fred and Ginger number from Follow the Fleet, but introduces something much more ominous: a phalanx of top-hatted, tail-coated, tap dancing men whose canes become first the guns of a firing squad, then the bars of a jail, encircling the beautiful, desperate couple as they twirl inside.

Arthur’s character put me in mind of a passage by Shirley Hazzard, appearing in her short story “A Place in the Country:”

After a pause, he said abruptly: “I think I told you I no longer loved my wife.”

“Yes,” she said.

“I only said that once, didn’t I?”

“Several times,” she answered, unaccommodatingly.

“Several times, then,” he agreed, with a touch of impatience. “In any case — I see now that I shouldn’t have said that. I mean, that it wasn’t true.”

She thought that the digressions in the minds of men were endless. How many disguises were assumed before they could face themselves. How many justifications made in order that they might simply please themselves. How dangerous they were in their self-righteousness — infinitely more dangerous than women, who could never persuade themselves to the same degree of the nobility of their actions.

Pennies from Heaven might be an argument against the ennobling effects of art. Arthur’s enthrallment with popular songs isn’t the expression of a poetic and misunderstood soul, the way it might have been in a more conventional story, but an evasion: a way of reinforcing the primacy of his own feelings and his own pleasure. He’s not too good for the world, he simply doesn’t want to accept its compromises and disappointments. The songs are a way of papering over his deficiencies as a human, akin to the way teenagers lean on song lyrics to lend grandeur to sorrows and rages they aren’t able to articulate. People like Arthur now are less likely to turn to popular songs as a shorthand for frustrated desire. What we have now is meme-world, which promises that nothing is ever serious and that anyone with the right set of references can play along.

“Pennies from Heaven,” the song, has a treacly “turn lemons into lemonade” message1 that pushes the movie’s title into high irony. One of the tasks of the 21st century has been to avoid mistaking irony and cynicism for depth, which makes me want to be cautious in my evaluation of this movie. But I think it’s also important to avoid romanticizing a highly reactionary time, to avoid its narratives of noble suffering and frothy escapism. The counterpoint to Arthur is the character of Eileen. She succumbs to a sad story and loses everything — but finds a way to make a harsh world work in her favor. If Pennies from Heaven is a tragedy, it’s not because of its characters, who lack the necessary nobility. Its tragedy might be in the songs themselves, which pretend both innocence and sophistication, and are far too easily sullied.

“Every time it rains, it rains / Pennies from Heaven / Don’t you know each cloud contains / Pennies from Heaven / You’ll find your fortunes falling / all over town / Be sure that your umbrella / Is upside down”

I think one reason for no remake might be that usually a (US style) remake takes something fun & makes it darker (riverdale) or takes something a bit dark & makes it way darker ( Fargo) or takes something weird & makes it unwatchable & uncanny ( Cats). I loved Pennies From Heaven, but I think it is about as weird & dark as it ever needs to be :)

A terrific essay, about a movie that had me spellbound when it came out. Thank you; looking forward to more.