Last month, reading some dreamy, fatalistic, anxiety-riven short stories by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, I thought to myself that Germans seem to write some of the best fairy tales, and the thought came to me again upon reading Thomas Mann’s imposing masterwork, The Magic Mountain, these past weeks. Perhaps this is because the tweeness that always threatens the genre is driven out and replaced by a beautiful dark dangerousness, a dangerousness that seems aesthetic as much as it is sensual.

In fairy tales, one of the greatest dangers is a place — an enchanted grove, a cave, a castle — that, due to some enchantment, exists outside of time. The story goes like this: an unsuspecting man wanders into such a place, in search of some treasure or delight. He lingers there, intrigued and seduced by it. He emerges, after a struggle, to find a hundred years have passed: his wife and children are dead, his town is destroyed or changed beyond recognition, and no one remembers him. Time, though he hardly felt it passing, has taken everything from him. This is roughly the story of Hans Castorp, the protagonist of The Magic Mountain.

Mann explicitly evokes fairy tales in his Foreword to The Magic Mountain (which I read in the translation by John E. Woods). He’s a little coy about it, explaining that its “once upon a time” is actually not so far in the past, but that it has “taken place before a certain turning point, on the far side of a rift that has cut deeply through our lives and consciousness.” The turning point in question is World War I, which, given the number of “turning points” and catastrophes society has suffered since then, plus some recent ones that are now top of mind, now feels very far in the past to us. I generally hate trying to argue that any past work is “relevant to today” — literature shouldn’t have to be au courant to be worthwhile — but I think that The Magic Mountain makes for particularly interesting reading for anyone who is feeling the effects of being pushed up against a societal turning point, or who is fearing more to come.

One thing that The Magic Mountain definitely doesn’t share with fairy tales: in no world could its story be appealing to children, or to anyone who isn’t up for 700 pages of Serious Intellectual Literature. He lets us know right at the beginning that he intends to take his time:

We shall tell it at length, in precise and. thorough detail — for when was a story short on diversion or long on boredom simply because of the time and space required for the telling? Unafraid of the odium of appearing too meticulous, we are much more inclined to the view that only thoroughness can be truly entertaining.

If you’re at all inclined towards the dish Mann is serving, let me say that it is, in fact, both thorough and entertaining. I found it a challenging and deeply satisfying read.

Mann attempts to bring his entire breadth of knowledge and intelligence to bear on what seemed, to many thinkers of his time, to be the question that superseded all others: how could a modern, “enlightened” society, one that valued progress and intellectual achievement, throw itself with such abandon into self-destructive violence?

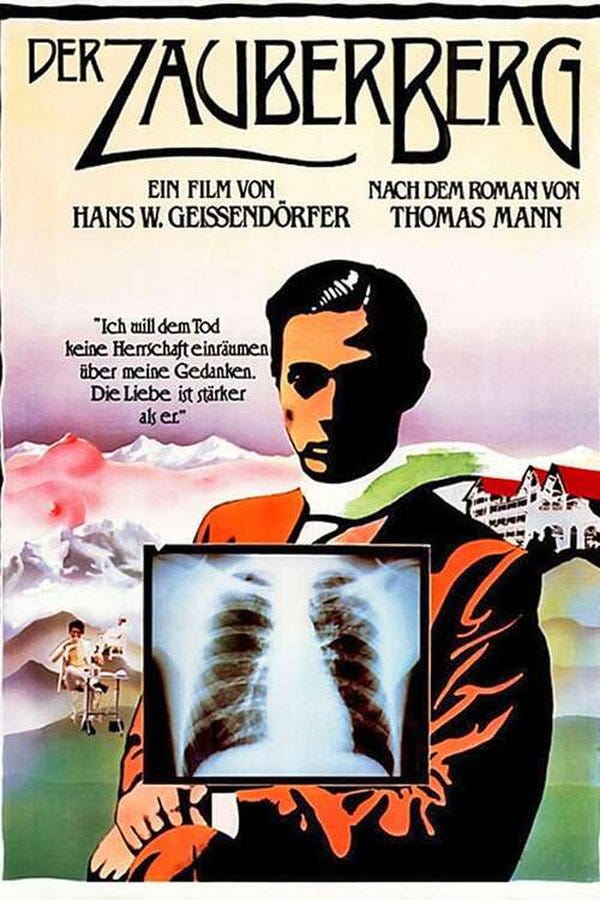

Rather than trying to write about all of society a la Balzac, Tolstoy, or Dickens, he approached the problem allegorically, by writing about a small set of characters in an isolated location: a sanitorium in the Swiss Alps, a sort of combination of hospital and resort where people with tuberculosis come to stay long term1, both with and without the hope of eventually being pronounced cured and permitted to leave.

The hero is Hans Castorp, who serves as a kind of everyman. Mann informs us near the beginning that there’s nothing very special about Hans; indeed, he repeatedly uses the word “mediocre” to describe him. He’s young, passably — but not brilliantly — intelligent, and has some vague ambitions to become an engineer in the field of shipbuilding (that this profession would keep him at sea level is, of course, metaphorically significant). He’s solidly middle-class, with enough interest from an inheritance to maintain him but not keep him in luxury. He doesn’t have strong family ties — his parents are dead — and not much passion for his chosen career. This means, most importantly for Mann’s purposes, that he’s impressionable.

Hans doesn’t have tuberculosis — at least, doesn’t believe he doesn’t — and when he takes the train up the mountain to the sanitorium, it’s to visit his sick cousin, who is a long-term patient there. Hans intends to stay there for only three weeks. At first, he’s unsettled and repelled by the strange behavior of the people there, their untidy appearance and lax manners, and the open conversation about ailments and bodies. He’s appalled that one of the managing doctors wears socks with sandals, and that a woman with a pneumothorax (an air pocket between the lung and the walls of the chest cavity) uses it to whistle at him on his walk. The inhabitants have their own jargon: a “Blue Henry” for the flasks used by TB patients to collect their sputum, and a “Silent Sister” for the thermometers without markings used to prevent patients from cheating on their temperature readings.

But soon, he finds himself adjusting to sanitorium life, which offers many comforts: five lavish meals a day plus a massage, and entertainment in the form of concerts and lectures. In particular, the cushioned lounge chairs, on which all patients take their mandated daily hours of “rest cure” — which is simply lying in the chair, doing nothing — turn out to be spectacularly comfortable.

The hours spent taking his rest cure on the lounge chair leave him lots of time to think, and he starts to wonder whether life in the sanitorium is really so bad. Society down in “the flatlands” starts to seem crude to him, the way they’re all obsessed with money, status, and their careers. Up on the mountain, where the days are strictly scheduled and all the practical aspects of life are prearranged for him, he can cultivate his mind and his sensibilities. But a man he meets there, an Italian philosopher named Settembrini (more on him soon) warns him against getting too comfortable:

Do you know what it means, my good engineer: ‘to be lost to life’? I know, I do indeed. I see it here every day. Within six months at the least, every young person who comes up here (and they are almost all young) has nothing in his head but flirting and taking his temperature. And within a year at the most, he will never be able to take hold of any other sort of life, but will find any other life ‘cruel’ — or better, flawed and ignorant.

Fate intervenes: in the days before his scheduled departure, Hans catches a mild cold and has to delay. He agrees to be examined by the head doctor, for formality’s sake, and — to no one’s surprise — the doctors promptly find a “moist spot” on his lung, a potential indicator of tuberculosis. Even though he has no symptoms beyond a chronically high temperature, they warn that for caution’s sake it’s best for him to remain for at least six more months. And Hans, it turns out, needs hardly any convincing to stay. Before long, he forgets that time is even passing. He spends his time developing his intellect, contemplating the new refinements of his mind while horizontal in his lounge chair, an activity he calls “playing king”. After a while, the idea of leaving seems impossible. And years of his life go by.

One thing I love about The Magic Mountain is that it combines a high intellectual seriousness with a barely-concealed current of deep sexual fucked-up-ness (the fucked-up-ness, if not the seriousness, is a quality it shares with The Good Soldier, which also takes place in a health spa and which I also love). One of the things keeping Hans on the mountain is the presence of the mysterious Madame Chauchat, a beautiful young Russian who explains to him that her illness gives her the freedom she desires: license to live apart from her husband, traveling Europe from treatment to treatment. He’s able to speak freely of his love to her for on one night only, the night of a masked ball, when he confesses his desire thusly:

What an immense festival of caresses lies in those delicious zones of the human body! A festival of death with no weeping afterward! Yes, good God, let me smell the odor of the skin on your knee, beneath which the ingeniously segmented capsule secretes its slippery oil! Let me touch in devotion your pulsing femoral artery where it emerges at the top of your thigh and then divides further down to the two arteries of the tibia! Let me take in the exhalation of your pores and brush the down — oh, my human image made of water and protein, destined for the contours of the grave, let me perish, my lips against yours!

Mann’s association of sexual desire with danger, ruin, chaos, and death is easily attributable to the fact that he spent his life closeted, and struggled deeply with homosexual desire from inside his heterosexual marriage. The seductive Clavdia Chauchat, in fact, is explicitly described in the novel as the female manifestation of a handsome male schoolmate with whom Hans was obsessed as a boy. It’s almost surprising to me the extent to which Mann let his desires come through in his fiction, how easily he allows those dots to connect. But I, of course, am a 21st-century reader, and it may not have seemed so obvious then. I’ll also note, with a smile, that preferred pronouns are highly significant to Hans and Clavdia’s romance: not gender pronouns, but formal vs. informal ones.

Much of the second half of the book is given over to philosophical discussions between two characters: the aforementioned Settembrini, who represents the humanist cause, and his debating partner Naphta, a Jesuit, whose philosophy is a bit more difficult to pin down. The chapters devoted to their discussions, in which they each advance their view of the ideal society and try to dismantle their opponent’s, are the most likely to try the reader’s patience — but if you’re a person who finds yourself using the word “neoliberalism” with any frequency, it’s worth paying close attention to them.

Settembrini’s views are easily recognizable to us: he’s fully in favor of secular liberalism, rationality, scientific progress, democracy, the power of literature, and individual freedoms. He believes that religious fanaticism, tyranny, ignorance, and conformism are enemies of full human flourishing, and is certain that the ideals of the Enlightenment, having vanquished the old medieval order, must ultimately prevail. Today he wouldn’t be called a humanist but a neoliberal.

Naphta, in turn, eloquently sets out to dismantle this worldview. Many progressive readers might find themselves nodding along to his arguments, which mirror a lot of what I read on twitter: that “Enlightenment” ideals are anything but ‘objective’ and ‘universal’ but are in fact riven with their own irrational biases; that emphasizing individual freedom over service to a greater cause results in self-devouring capitalism; that education is not a mechanism for societal advancement but rather for the maintenance of a bourgeois order founded on property and capital; that the revered ancient Greeks were just one civilization of many; that there’s no basis to see ‘health’ as distinct from and superior to ‘sickness’, or ‘reason’ as superior to ‘feeling’.

Readers who sympathize with these points, however, will probably balk at Naphta’s conclusions: that the best, most natural (and thus inevitable) human society is an authoritarian one, grounded in religiosity, obedience, and violence. He claims that Marxism, though it claims to be scientific, is really an expression of the wish, deep down, for a return to the old religious order.

But in the end, neither philosopher “wins” — another force arrives at the sanitorium, a man with a loud voice and wild “flaming” hair, who is given to long rambling speeches that go nowhere in particular, and who immediately commands, through sheer force of personality, the attention of everyone around him. I think Mann intends him to be a stand-in for the monarchy, or at the very least a kind of persuasive personality-driven anti-intellectualism. Though The Magic Mountain was published in 1924, I’m probably not the only reader who sees a resemblance to a particular, very 21st-century figure. The philosophers are infuriated by his presence, how he subsumes everything around him and seems to render all their careful arguing irrelevant. “He’s just a stupid old man,” says Settembrini. “What do you see in him?” But Hans is entranced, beyond all reason.

In the book’s final act, we see a portrait of decadence, of the world on the precipice of catastrophe: the population first in torpor, obsessed by card games and trivial hobbies, then in thrall to a woman who appears to have psychic powers, then an eruption of undirected aggression:

What was it, then? What was in the air? A love of quarrels. Acute petulance. Nameless impatience. A universal penchant for nasty verbal exchanges and outbursts of rage, even for fisticuffs. Every day fierce arguments, out-of-control shouting-matches would erupt between individuals and among entire groups; but the distinguishing mark was that bystanders, instead of being disgusted by those caught up in it or trying to intervene, found their sympathies aroused and abandoned themselves emotionally to the frenzy.

Mann is describing, of course, not just the inhabitants of the mountain but a society careening towards war. Here he seems to throw up his hands: philosophical debate didn’t help, knowledge and study didn’t help, science didn’t help, the great works of art didn’t help — nothing high-minded, in the end, could stop “the deafening detonation of great destructive masses of accumulated stupor and petulance” that was World War I.

And he didn’t know then, but there was more to come a couple of decades after that, and even more after that. Just like Hans’s doctors, Mann cannot make a clear diagnosis.

We know now that sanitoriums could never cure tuberculosis, beyond providing the general benefits of rest, nourishment, unpolluted air, and the placebo effect. The greater mistake, Mann suggests, is in continuing to think that ideals, no matter how well-reasoned and beautifully argued, can cure society.

This is an excellent piece in the New York Times on the history and architecture of TB sanitoriums in Europe.

Ohhhh, a wonderful piece, thank you! I haven't read MM but listened to an audio book version last year which I thoroughly enjoyed. While travelling in Estonia earlier in the year I stayed on the Baltic coast and came across a still open Soviet-era sanatorium, I fantasied about meeting up with Hans C for a coffee and a quick cigarette ; )

https://nexus-instituut.nl/en/essay/the-quest-for-vision