“Civilization has distributed men among three basic types,” writes Balzac in the opening of his Treatise on Elegant Living, a short (and unfinished) guide to beautiful living. The types are as follows: the man who works, the man who thinks, and the man who does nothing. As he will make clear, elegance is the purview only of the third. In his accounting of “those who work,” which includes both manual laborers and successful professionals, elegance is forever out of reach:

By the time they reach the age of rest, the sense of fashion has been obliterated and the time of elegance has slipped away, never to return. Consequently the carriage that takes them around has a projecting running board with a variety of purposes, or is decrepit like that of the famous Portal. With them, the prejudice for cashmere lives on; their wives wear diamond rivières and girondoles of jewels; their luxury is always an investment; in their homes, everything is well-to-do, and you read above the theater box: “Speak to the attendant.” If they count as numerals in the social circle, then they are single digits.

From context, you can tell that cashmere, diamond rivières, and carriages with running boards may be costly, but inelegant. One of the things I love about reading Balzac and Proust is their attentiveness to these markers of fashion and class. Balzac may have dressed terribly, but he understood the importance of clothes.

He goes further with the idea that a working life is incompatible with an elegant life, by asserting that elegance can only arise from a restful life. His proposal, in a set of aphorisms that almost form a syllogism:

The goal of the civilized man as of the savage is repose.

Absolute repose produces spleen.

Elegant living is, in the broad acceptance of the term, the art of animating repose.

The man accustomed to work cannot understand elegant living.

In short, elegance is something that arises in order to avoid the depression that comes from idleness: it’s an animated, an interesting, a beautiful idleness. And it costs a lot of money. He carves out an exception for artists, for whom work and “animated repose” are the same, and who cannot help but be elegant (although, presumably, they benefit from a circle of patrons and wealthy friends). He then offers a number of glib definitions of elegance, including “the art of spending one’s income as a man of wit.”

For Balzac, the emergence of the ideals of elegant living coincide with the ascendency of Napoleon:

And in the year of grace 1804, as in the year MCXX, it was acknowledged that it was infinitely pleasant for a man or a woman to say to themselves when looking at their fellow citizens: “I am above them, I dazzle them, I protect them, I govern them, and every one of them can clearly see that I govern them, protect them, and dazzle them; for I am a man who dazzles, protects, or governs others, who speaks, eats, walks, drinks, sleeps, coughs, dresses, and enjoys himself differently than those dazzled, protected, and governed.

And ELEGANT LIVING suddenly appeared!…

And it soared, bright and new, utterly old, utterly young, proud, spruce, approved, corrected, augmented, and restored by this wonderfully moral, religious, monarchic, literary, constitutional, egoistic argument: “I dazzle, I protect, I…” etc.

For the principles by which people of talent, power, or money conduct themselves and live shall never resemble those of the common herd!…

And no one wants to be common!…

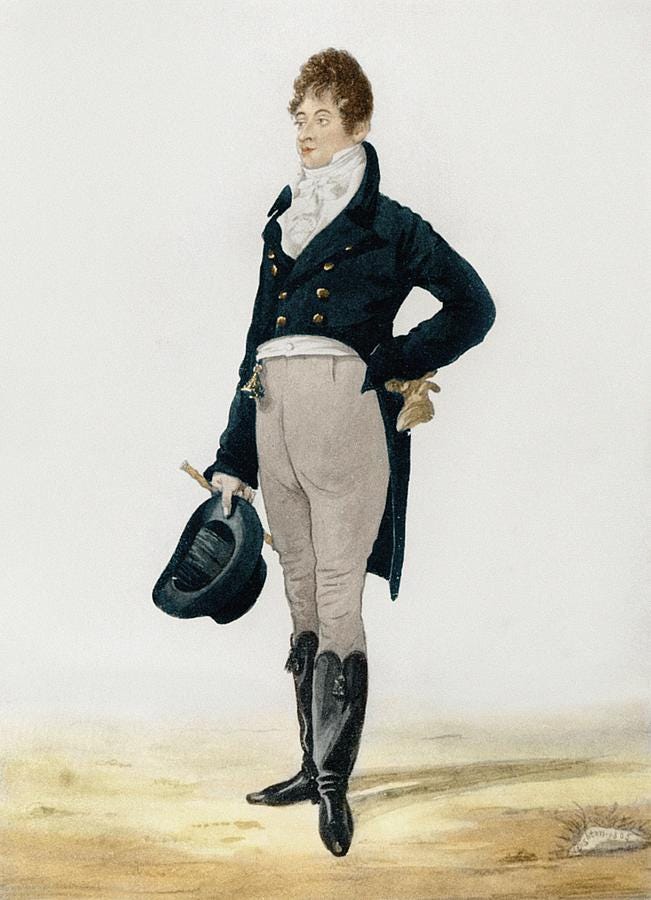

Balzac was writing in 1830, post-Revolution and post-Napoleon, although further revolutions were on the way, including the July revolution that same year. The aristocracy was on its last legs and consumer capitalism was taking hold. Balzac’s archetype of elegant living, Beau Brummell (a fictionalized version of whom makes an appearance in the pamphlet), cultivated aristocratic manners and became the most fashionable man in Europe without any aristocratic pedigree.1 As the treatise’s scholarly introduction by translator Napoleon Jeffries describes him, his elegance was comparatively democratized, although still very expensive:

…for if he acted the aristocrat, lived the life of an aristocrat, and was courted by the aristocracy, Brummell was no aristocrat. He was a new kind of autocrat, natural-born in that he came from no family (to his middle-class family’s understandable chagrin), and sired none; he was for all intents and purposes a self-sired autocrat, whose example in dignified manners, elegant dress, and stoic distinction could eventually be followed by members of any class and occupation — provided, of course, they had access to a sufficient amount of funds to maintain a life of leisure.

Although many of the specific fashionable details in the Treatise on Elegant Living are no longer useful to someone seeking to be elegant in the 21st century, I was struck upon reading it how much of our current consumerist anxieties are still reflected in its pages. The bourgeois couple with the carriage with the running board, if living today, would probably live in the kind of McMansion that gets lampooned on McMansion Hell. No one browsing lifestyle tips on Instagram wants to be the kind of parvenu who has lots of money and terrible taste; no one wants to look cheap or old-fashioned; no one wants to inherit their grandmother’s inelegant heavy bedroom set.

In the advice that the fictional Beau Brummell dispenses in the treatise, we see many resemblances to the kind of elegance advocated by more modern stylists: simplicity is better than excess, “natural” effects are better than belabored ones, freshness is better than being out-of-date, and a kind of studied carelessness or sprezzatura is the ultimate aim. This, of course, is much more difficult to achieve than simple luxury. Some of pretend-Brummell’s tips:

*

Anyone who does not frequently visit Paris will never be completely elegant.

*

The most essential effect in elegance is the concealment of one’s means. Anything that reveals thrift is inelegant.

*

A profusion of ornament works against the intended effect.

*

A multiplicity of colors will always be in bad taste.

*

Studied elegance is to true elegance what a wig is to hair.

*

Negligence of clothing is moral suicide.

*

The boor covers himself, the rich man or the fool adorns himself, and the elegant man gets dressed.

*

A rip is a misfortune, a stain is a vice.

Balzac also takes pains to distinguish between the old aristocratic manners and the new, elegant ones. One big distinction: while noble dynasties pass down furnishings, tableware, and other effects through generations, the new elegance requires that such items be frequently replaced. A chair or a set of silverware, for an elegant person, should be simple but absolutely up-to-date, to remain in keeping with fashion. Another difficulty for the elegant person: cleanliness and upkeep are necessary, but over-protectiveness of your luxurious items signals bad taste. Furniture or rug covers taken off only for parties are decidedly inelegant. The elegant person, faced with a wine stain, simply shrugs and replaces the blouse or the sofa as needed.

These days, people like to say — rather glibly — that “good taste” consists of whatever rich people are doing, nothing more or less. But even tongue-in-cheek treatises on taste like this one show that it’s more complicated than that. Balzac was writing at a time when the strictures of “good taste” had, within recent memory, been cracked open by the downfall of the aristocracy. Good taste requires money, yes, but also an ineffable something else, something achievable by artists and social strivers but not by bankers (for whom, he asserts, elegance must always be out of reach, alongside businessmen and “teachers of the humanities”). For Balzac, it requires also an elevation of the mind, careful study, a devotion to inner perfection — accessible to everyone, but achievable by only a few. Brummell himself couldn’t sustain his position forever: he spent wildly beyond his means, fled to France to avoid creditors, and died in poverty.

If Balzac draws a two-dimensional picture of social status (there’s wealth, and then there’s elegance) in the 20th century and beyond we have a third dimension, that of coolness, which is a sibling to elegance but certainly not the same thing — and considerably less expensive (although, again, it’s easier to be cool if you have money). It’s a property of coolness that no one can quite write about it seriously, because that would be uncool; all writing that attempts to define it also maintains a critical or ironic distance from it. All we can do is read Blackbird Spyplane (or whatever else counts as cool in our specific circles), which is constantly in tension between the necessity of an anti-capitalist ethos to be cool, and the fact that it is fundamentally a consumerist enterprise. The constant: we all admire the appearance of effortlessness, and scheme endlessly to pay for it.

Brummell was also, if you’re very online, the subject of a somewhat unhinged twitter thread blaming him for the current dullness of men’s fashion, the archetypal example of Buckle Up twitter.

OMG do you just love the parts of Proust where he finally meets Mme de Villeparisis and Bergotte--these authors he has loved--and realizes they are NOT AT ALL COOL! That they are writing about cool stuff from such a distance, such a remove, and that there mere fact that they are ambitious writers sort of disqualifies them from ever truly being a part of fashionable society. Admittedly, Proust's novel is in part about the change in social mores that allows, say, an insufferable bourgeois Mme. de Verdurin to start running a fashionable salon in 1920--an idea that would've been unthinkable in 1890.

I think people can successfully write about being cool if, like Proust, they've retreated from society and are in no way any longer attempting to be cool themselves =]

Very cool piece, I really enjoyed it! You could see the grandparents of a lot of modern ideas about style and elegance and money in this one. I especially enjoyed that the idea of stealth wealth was still present even back then. I think elegance might be out of the running for me by these definitions, because I’d rather have the hand-me-downs than have to keep updating perfectly good things to stay relevant/elegant.

Much like Ken, this felt a tad satirical to me. Almost like a 19th-century Preppy Handbook. Is that just a misreading of the tone do you think?