Travelogue: Chamonix, Burgundy, Alsace, Berlin

Also: outdoorsiness, connoisseurship, Altarpiece of Isenheim

After a few weeks as a tourist (France) and a business traveler (Berlin), I’m back home in Seattle and resuming my regular life. Here’s some of what I got up to.

Chamonix

Chamonix is a ski town that sits at the foot of Mont Blanc, in a valley nestled against the Swiss border. I was there with my mother on a group hiking trip of mostly Canadians, and we spent our days tromping through scenic alpine landscapes.

As a rule, I’m not an outdoorsy person, and I resent any activity that necessitates a trip to REI to buy specialized gear (this tends to put me at odds with Seattle and the whole Pacific Northwest as a concept). Outdoor gear annoys me: its ugliness, its costliness, its bulkiness, its uselessness outside of specific contexts, and the way others judge you for not having it, or for having the wrong kind. The way that outdoorsy types will characterize “city” activities as decadent or frivolous, and “being in nature” as intrinsically moral, healthy, and worthy, also annoys me.

But these objections are petty, and they dissolved for me in the face of the landscapes themselves: glassy lakes, grand vistas, delicate alpine flowers, herds of sheep with bells on, the sight of the toy town below. And Mont Blanc itself, the peak looking like big dollops of whipped cream on top of a cake. Vigorous walking in a beautiful place really does feel healthy. The city person in me also appreciated mountains with amenities: at every altitude, there was a place to get a drink.

Burgundy

From there my father joined us and we drove to Chateauneuf-en-Auxois, a village in Burgundy outside of Beaune.

One of the main things to do in Burgundy is drink wine, although some hasty research when we got there showed that the wineries aren’t really set up for tourists, and Burgundy wine prices are rough on the budget. Still, we arranged a wine tasting.

I’m a wine-enjoyer but not much of a connoisseur. I’ll happily drink pretty much anything, and I don’t know much about the various varietals and regions and what they’re known for, or what wine should be paired with what food. Still, I really appreciate the act and ritual of wine tasting as an experience that rewards attention and connoisseurship.

I wound up thinking about how the experience of drinking wine changes during a wine tasting, how even the flavor changes when you’re asked to turn all your attention and perceptiveness to what you’re drinking. I have a lot of respect for connoisseurship as an ethos (as opposed to the collector’s impulse, which I find creepy) and started trying to define it for myself. Activities that lend themselves to connoisseurship are primarily sensual or experiential, and the experience deepens, rather than exhausts itself, with increased experience and attention. Becoming a connoisseur means gaining experience in order to train oneself, over time, to perceive finer and subtler distinctions between different instances — and then having the pleasure and enjoyment actually heightened through this understanding.

There’s a moment after a while when the connoisseur’s preference shifts away from what’s broadly appealing and toward what’s interesting. This is where the accusations of snobbery tend to come in: one of the effects of developing “taste” is that it becomes harder to enjoy the simpler, more broadly appealing stuff, even while recognizing what makes it appealing. I feel kind of bad about this myself. I used to say that I never wanted to become the kind of person who couldn’t enjoy a student production of The Magic Flute, but now I’m someone who unfairly neglects my local, well-regarded opera company because I’ve been disappointed too many times.

One of the accusations leveled at wine connoisseurs is that “taste” is all in their heads. There are all the stories about blind taste tests where it’s revealed that the experts can’t identify what they’re drinking in the absence of other cues. From this come accusations that their knowledge is worthless, that distinctions between wines are nonexistent, that the entire field is one of price inflation and status-jockeying.

I don’t doubt that this is real; we know that humans are nothing if not suggestible, and the links between “good taste,” money, oppression, and class are well-established and unflattering. The wine world, in particular, is full of fraudulence, corruption, and price manipulation. But it also strikes me as exemplifying the tenets of philistinism. Philistinism asserts that the subtleties and distinctions experienced by connoisseurs are either invented or unimportant, that people who enjoy something with less obvious appeal are deluding themselves or playing status games, that attention paid to esoteric details is attention wasted, and that surface likeability (or other clearly defined social utility) is the primary or only criterion of value.

My complaints above about “outdoorsiness” are themselves an expression of a philistinist mindset. The gear is ugly and worthless! I complain. But actually, good boots help a lot.

My feeling at the tasting in Burgundy, going from the “village” wines to the Grand Cru, was something like: c’mon, of course you can tell the difference. I knew that I was drinking something entirely different from the $12 bottles I buy at home. I don’t know a lot about wine, but it tasted real to me.

Alsace

Alsace is the region of France that lies between the Vosges mountains and the Rhine river. Its location, between two “natural” borders of strategic importance, meant that it was fought over, changing hands many times between France (roughly defined) and Germany (roughly defined). Most recently, it was occupied by Hitler during WWII before being returned to France after the defeat of the Nazis. There are memorials to the malgré-nous (meaning “against our will”), the men from Alsace and Lorraine who were conscripted into the German army during WWII and sent to the eastern front.

Alsace doesn’t quite feel French, for reasons that are easy to understand. Google tells me that it has its own legal code combining aspects of French and German law, not unlike Quebec’s special legal status inside Canada. The names of the towns sound Germanic, the cuisine is more potato and sauerkraut-forward, and the historic buildings are half-timber rather than stone. In contrast to elegant, self-serious Burgundy, Alsace was cheerier and kitschier. The half-timber houses in Colmar, where we stayed, are painted in various pastels, which is apparently a relatively recent change meant to make the city look cuter and more appealing to tourists.

The Altarpiece of Isenheim

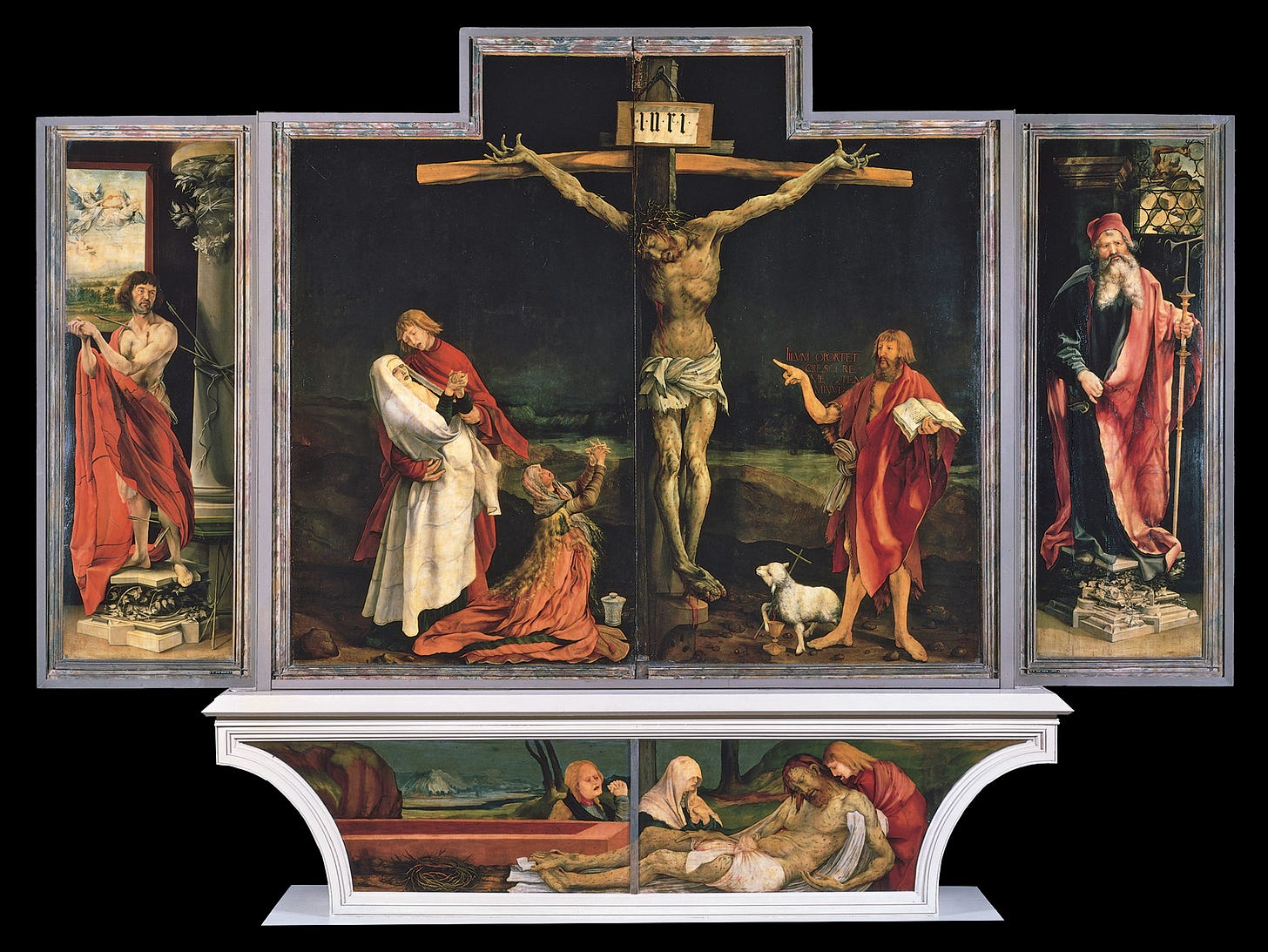

My parents’ guidebook claimed that the Altarpiece of Isenheim, an elaborately painted and multi-paneled work by Matthias Grünewald, is as familiar to Germans as the Mona Lisa is to Americans. It certainly doesn’t draw the kinds of crowds the other work enjoys, and most people I spoke to hadn’t heard of it. I became interested after reading about it in The Man Without Qualities, where it’s described as one of the masterpieces of German art.

I didn’t remember then that Sebald also wrote about it in The Emigrants, in this late passage:

About ten or eleven in the evening I arrived in Colmar, where I spent a good night at the Hotel Terminus Bristol on the Place de la Gare and the next morning, without delay, went to the museum to look at the Grünewald paintings. The extreme vision of that strange man, which was lodged in every detail, distorted every limb, and infected the colours like an illness, was one I had always felt in tune with, and now I found my feeling confirmed by the direct encounter. The monstrosity of that suffering, which, emanating from the figures depicted, spread to cover the whole of Nature, only to flood back from the lifeless landscape to the humans marked by death, rose and ebbed within me like a tide. Looking at those gashed bodies, and at the witnesses of the execution, doubled up by grief like snapped reeds, I gradually understood that, beyond a certain point, pain blots out the one thing that is essential to its being experienced — consciousness — and so perhaps extinguishes itself; we know very little about this. What is certain, though, is that mental suffering is effectively without end. One may think one has reached the very limit, but there are always more torments to come.

Most of the writing about the altarpiece focuses on its primary image, the Crucifixion. Even by crucifixion standards, it’s gruesome: the details like the dislocated shoulder and the fingers contorted in pain are sickening. But there are other details that set it apart: it was built for a hospital, and the sores on Christ’s yellowing body are characteristic of a disease then known as St. Anthony’s Fire, contracted by eating tainted rye bread. The idea was that patients, seeing a version of Christ suffering from symptoms similar to theirs, might be humbled or consoled.

The other panels are not so gruesome, but they’re vivid and disturbing in different ways. The panels showing the Resurrection and the Concert of Angels are almost hallucinatory and linger at the border between beauty and garishness. Another panel shows St. Anthony menaced by monsters.

More wine

We also went to a wine tasting in Alsace. Again, the experience was very different from Burgundy. The winery representative acknowledged that Alsace doesn’t get a lot of love from wine connoisseurs and international collectors, but that Alsatian winemakers are freer to experiment and adopt new and more environmentally friendly methods (organic, biodynamic, etc). She also implied, very very lightly, that Burgundy’s wine industry is in the process of being ruined by private equity, while Alsace, the scrappy underdog, is getting better all the time.

The wines were lovely.

Berlin

This was a work visit and I didn’t have much free time to spend in Berlin this time around, but I wrote about my impressions on my first visit earlier this year (Part One, Part Two). I enjoyed myself more this time around, partly due to the nicer weather and partly due to staying in the hip Prenzlauer Berg rather than the barren area near the Östbahnhof.

My work team had two “bonding” events: one dinner at the ultra-kitschy Hofbräu Wirtshaus, and one at an axe-throwing venue. The former featured Lederhosen, enormous beer steins, sausages, and a live band with an accordion. The latter, though I suspect it’s meant to make patrons feel like Viking warriors, felt like pure San Francisco. It all felt difficult for me to understand; all cultures have contradictions and complexities, but despite reading a lot of German literature lately I had a hard time getting my head around it, the kitsch and the dreary 19th-century art and the Christmas markets and the hallucinatory 16th century Christ and the Schubert lieder and the Nazis. France feels graspable to me, Germany does not. I’m sure this is a failure in my own capacity to perceive and understand both countries.

I didn’t make it to the opera this time but did go to see the Berlin Philharmonic play Strauss and Beethoven. One of my American coworkers asked if I could really hear the difference between an ordinary orchestra and one like the Berlin Phil. My answer, like the wines, is: c’mon, you can tell.

Books

My reading material during the trip:

The World of Yesterday, Stefan Zweig

Boredom, Alberto Moravia (newsletter piece)

The Passion According to G. H., Clarice Lispector

The Fraud, Zadie Smith

I imagine the Berlin Phil performing their countrymen Beethoven and Strauss with an extra something special!