Jeremy Denk’s piano memoir Every Good Boy Does Fine is a rare thing: a true künstlerroman, an artist’s coming-of-age story that is first and foremost about the art, and only secondarily about childhood and identity and family (except, of course, as they pertain to the art). The most important relationships in the book are with his piano teachers, not with parents or romantic partners, although they certainly play a role. Furthermore, Denk approaches the subject of his art — the piano and the great music written for it — without a hint of irony, cynicism, or malice. The only composer he can bring himself to disparage is Clementi, and then only very mildly.

What is present instead on the page is love, and infectious eagerness. He loves Mozart and Beethoven and Schubert and Chopin and Brahms and wants the reader to love them, too. Since any reader inclined to pick up this book at all probably already feels as he does, he could have been a lot lazier about it than he is.

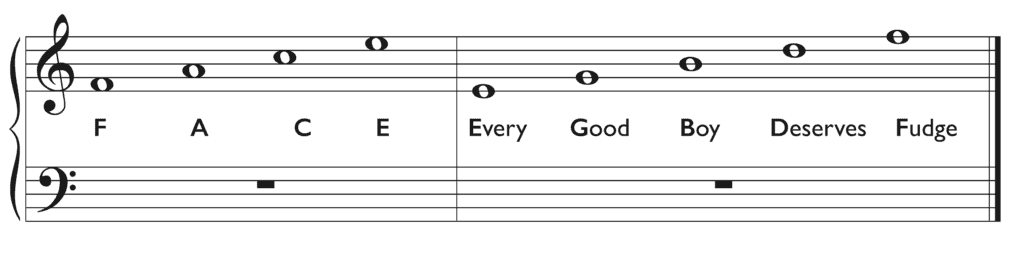

The book is an expansion of Denk’s 2013 piece for the New Yorker of the same title. I loved the piece and wrote my own (much poorer) version in this newsletter. The title refers to the mnemonic that beginner pianists use to remember which notes are on which line of the musical staff in the treble clef (although I learned it as “every good boy deserves fudge — “father Charles goes down and ends battle” doesn’t make it in). The book retains all of what’s in the article, but adds a lot more specifics about repertoire, music, and technique.

There’s the requisite amount of struggle: a capricious and skeptical father, an alcoholic mother, other kids who think he’s a nerd (he is) and, at times, the fear that there won’t be enough money for music school. He’s also gay, although it takes him until the end of the memoir at the age of 30 to figure that out, and in the meantime there are a series of nice, frustrated girlfriends who are bemused by his sexual ambivalence. All these things are taken lightly; his overall tone is that of someone who knows he’s been very lucky and is grateful to be spending his life doing the thing he loves best.

The primary struggles, however, are the musical ones. How to handle the dotted rhythms of the second movement of the Appassionata sonata? And get just the right timbre in the opening of Brahms’s D minor sonata for piano and violin? And navigate the leaps in the Mozart concerto K. 415? There are also physical issues, when he suffers an injury involving the fourth finger of his right hand (an injury which, for pianists, has some frightening historical resonances). He trusts the reader to stay with him through discussions of piano technique and artistry, of the minute decisions that go into rendering specific musical moments, and in these stretches is never condescending. As an amateur pianist, I absolutely ate all of it up. The discussions of musicianship already inform my own playing and mirror what my teachers have said to me: the importance of slowing down, paying attention to every detail, and, more prosaically but most importantly, reading the actual markings in the score.

He alternates the chapters of his life story with some discussion of the three primary elements of music: harmony, melody, and rhythm. As many enthusiastic teachers do when explaining something technical to a lay audience, he often runs the risk of being a bit too twee (in an early chapter on harmony, he describes a mild dissonance, which wants to move to resolution but only weakly, as analagous to the experience of wanting to get some ice cream from the fridge but being too lazy to get up off the couch). He’s most interesting when he allows himself to get a bit philosophical — “It seems to me that one of melody’s (and by association music’s) most central virtues is this merging of memory and action in a single gesture,” he writes, an idea I’ll be thinking about for a long time.

The book is an absolute delight when describing his teachers, whom he renders in wonderful Dickensian strokes. There’s the austere and ironical Bill, whose house has very little furniture outside of a magnificent Bösendorfer with extra keys. There’s a cigar-chomping, unsentimental Julliard professor, who curses at him in great streams before handing him a bottle of scotch. And, most significantly, there’s the three-piece-suit wearing Hungarian master György Sebők. This is the scene from the New Yorker piece that sealed the deal; I knew from this that I wanted to read the book:

Sebők listened to her play as if he were tired of teaching and hoped to experience the music for its own sake. At last he couldn’t take it anymore, and demonstrated a few measures. In his mands, the music was not just morose but poisonous. There was a stunning distnce between his eloquent hesitations and the student’s aimless aimlessness. He stopped playing in the middle of a phrase, and we all knew that something special was about to happen.

Then he said, “To show love for someone, but not to feel that love” — long pause — “that is the work of Mephistopheles.”

Hanging with the smoke in the dimly lit room, that fantastic remark verged on camp. … But Sebők made no further explanation. “That is enough for tonight,” he said. I spoke to some of the German and French students out in the hallway, stupid with excitement. “Can you believe that?” I asked. Then I couldn’t help myself — just like in music — and went too far. I tried out a Hungarian accent and said, “That is the work of Mephistopheles.” And they looked at me like, You Philistine, how dare you imitate him.

If the book has a weakness, it’s named in the title: Denk is a Good Boy, who was once one of those high school students who excels in everything, his teachers all convinced that their subject is the one he likes best. Like many such children, he wants very much to delight and to please, and this makes his narrative occasionally tip over into the puppyish. But those moments are rare, and he mostly accomplishes his aim: in this book, he is so damn likeable, and has a conversational, self-deprecating, literate and just-erudite-enough style to make reading him a pleasure and a breeze. It made me wish I’d been more serious about the piano when I was younger — rather than a hard struggle, the book made me feel like I missed out on many joys.

There’s an appendix with recommended recordings of each piece he discusses, so the reader can follow along and hear the musical moments he describes. One of the animating forces behind the book is the same one that lies behind the youthful mixtapes made for friends and crushes. I remember very well that same hopeful act: compiling the music I love, trying to get others to listen to it, and pointing out the best moments in hopes that they might, finally, hear the beauty that I hear.