Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation — marked by a quiet unflagging intensity — is the kind of film on which reputations for mastery are made. Not that the man needs any more acclaim; still, out of his best-known films, the average person is far more likely to have seen The Godfather or Apocalypse Now than The Conversation, which is a pity. While The Godfather sprawls, The Conversation is precise and economical; while The Godfather is loud and bloody, The Conversation is quiet and (nearly) pristine. And while “Hitchcockian” is a word you’d never apply to Apocalypse Now, it’s one that fits perfectly here. There was supposed to be a theatrical re-release in 2020 with a new restored print, but, well, you know.

In the first scene of the movie, we hear the conversation of the title. Two people are walking in circles in San Francisco’s Union Square, a shy young woman and a nervous, bespectacled man. From a few lines we gather that they are lovers, and that they are likely having an illicit affair. And then we see that they are observed — someone directs a telescope at them from a window, and in a nearby white van, Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) is listening to what they say. Their talk seems banal, inconsequential. But throughout the movie its lines are called back again and again, like musical leitmotifs:

I don't know what I'm gonna get him for Christmas yet. He's already got everything.

You're supposed to tease me, give me hints, make me guess, you know.

Every time I see one of those old guys, I — I always think the same thing. I always think that he was once somebody's baby boy, and he had a mother and a father who loved him.

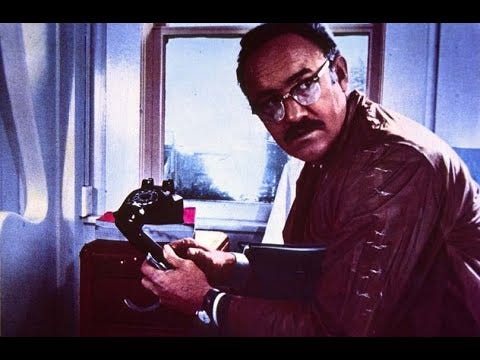

Harry Caul, making his recording in the van, is one of those skilled protagonists who often feature in thrillers: we don’t know why he does what he does, but we know that he’s very good at it. Soon, we see that it’s all he does. He seemingly has no friends or family, even claiming not to have a phone. His apartment is heavily secured but devoid of personal items. And, crucially, he has no conversation of his own. His encounters with people are characterized by awkward silences and hesitations. He asks few questions — perhaps so that no one will expect answers from him in turn. The only thing he does for fun is play the jazz saxophone, in his apartment, alone.

He also rigorously separates his work — the business of making recordings of people who think their words are private — from any thoughts about the meaning or consequences of that work. He doesn’t care who they are or what they’re saying, he tells a colleague. He has no insight into human nature. He just makes the recording, and the rest is someone else’s business. And in addition to this, or because of this, we come to see that he is a man of integrity and strong principles.

The fundamental question of the movie: is Harry a good man, a moral man? And when his work is turned to sinister ends, what is the right thing for him to do?

*

Once, I took an English Literature course in which we read Thomas More’s Utopia. One of the concerns of the age, the professor explained, was the question: does a philosopher have a duty to engage in public and political life, using their knowledge to work for the betterment of all? Or is it better to retreat from the corrupting influences of the world, resist all temptations of fame and power, and devote oneself to a life of contemplation? The Utopia described is, in part, a place where a good person does not have to choose between the two. The professor used the terms otium — an old Latin word meaning something like retirement or leisure — and negotium, literally the negation of that state. In modern Italian the similar word negozio is a noun referring to a shop or store. Negotium, the business of working, is intricately connected, no matter how noble, to the language of the marketplace. Negotiation.

Which is more moral, the better choice for someone who wants to be a good person? Contemporary activism certainly favors negotium. Its call for action (with words like amplify, resist, speak out) includes a warning: to fail to act is by nature to be complicit in the wrongs of others.

But alongside it there have always been arguments for the reverse. To act is always to seek influence, to use one’s power to compel others to act in a way they might not otherwise. Motives that start out pure often prove to be corruptible. Holy leaders of all kinds have preached the merits of withdrawing from society and all its ills, as have people with a separatist bent from both ends of the political spectrum.

Otium doesn’t quite mean solitude, but many thinkers have treated the two as entwined. In his essay On Solitude, the 16th century philosopher Michel de Montaigne enjoins:

We should set aside a room, just for ourselves, at the back of the shop, keeping it entirely free and establishing there our true liberty, our principal solitude and asylum. Within it our normal conversation should be of ourselves, with ourselves, so privy that no commerce or communication with the outside world should find a place there.

*

Harry’s work is itself a kind of solitude — if he’s good at his job, his presence in the lives of others is undetectable.

He guards his solitude partially for his own safety and the integrity of his work, but more importantly to absolve himself from sin. We learn he is a devout Catholic who will not take the Lord’s name in vain; we see him go to confession in anguish, worrying that his work may be used to harm others. If he can keep enough distance between his work and the world, insulate himself from as much knowledge about other people as possible, he might, he hopes, keep himself blameless. And so he strives to contain and conceal his aching loneliness.

In one scene, he asks a woman if, hypothetically, she could be with a man who tells her nothing about himself. “But how would I know if he loved me?” she asks. “You’d have no way of knowing,” he replies, in pain.

Hackman plays Harry with a kind of slumping mildness, a kind smile, someone we feel has a deep personal reluctance to do harm. He seems like a soft-spoken engineer of the kind I encounter frequently in software companies, someone who enjoys building his own equipment and fiddling and tweaking in his workshop, someone for whom otium is the clear ideal. The Conversation wisely leaves out Harry’s backstory, save one dark event, so we don’t know how he got into the business. In some ways he’s perfectly suited for it, and in other ways it’s all wrong.

The movie has a representative, too, for negotium: Bernie Moran, a rival wiretapping professional, “the guy that told Chrysler that Cadillac was getting rid of its fins.” Bernie openly boasts about his influence, implying that his work was decisive in a recent presidential election. He hawks his equipment at trade shows with the assistance of a booth babe, a woman in white go-go boots and an aggressively blonde hairpiece. He gives out free pens and wears a blazer branded with his own name.

Surely it’s better to be like Harry than like Bernie, if you have to choose?

*

The other favored use of otium, that state of freedom and solitude, is to devote oneself to a grand project with which one will re-enter the world: write the novel, finish the painting, hone one’s craft through study. Montaigne in On Solitude disapproves of this aim: “As far as I can see, those authors have withdrawn only their arms and legs from the throng: their souls, their thoughts, remain even more bound up with it. They step back only to make a better jump, and, with greater force, to make a lively charge through the troops of men.” If the irony of putting this passage in one of the essays — which he published during his lifetime and through which he attained lasting fame — ever occurred to him, he doesn’t mention it here.

*

The Conversation is something of a slantwise Rear Window. In both films, we have a man observing others without their knowledge — one for his job, and the other for pleasure, during a period of enforced leisure. Both of them observe something that may or may not point to murder. But in Rear Window we have no trouble taking Jimmy Stewart’s side: he sees the evidence of a crime, he turns out to be right, then he valiantly intervenes and saves the day. Some moral ambiguity exists, in the form of a little finger-wagging about voyeurism, but it’s shrugged off quickly.

But in The Conversation, everything is murkier. Harry can’t save the day; he’s the one who committed the fatal words to tape in the first place. And he can never be certain that he’s correctly interpreted what he hears.

There’s a plot twist near the end that I experienced as a disappointment, the kind of twist that seems to brush away the questions raised during the movie for the sake of a cheap surprise. After thinking on it more, I still don’t like it, but I admit that even in its cheapness, it complicates the question of the film: which course of action is the moral one? When we intervene in a situation we do not fully understand, how can we be sure we are doing good?

I’ll say without spoilers that the final scene is perfection. It features a permanent rupture in Harry’s prized solitude, the intrusion of another presence into his life. And with it, a contamination that no amount of cleaning can remove.

Have you ever seen The Parallax View? I think a good number of thrillers from that era are still v much worth watching.