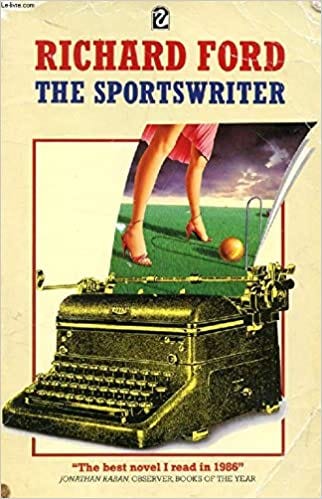

Avoiding the Question

Richard Ford's The Sportswriter

On the first page of Richard Ford’s 1986 novel The Sportswriter, we learn most of the salient facts:

My name is Frank Bascombe. I am a sportswriter.

For the past fourteen years I have lived here at 19 Hoving Road, Haddam, New Jersey, in a large Tudor house bought when a book of short stories I wrote sold to a movie producer for a lot of money, and seemed to set my wife and me and our three children — two of whom were not even born yet — up for a good life.

Just exactly what that good life was — the one I expected — I cannot tell you now exactly, though I wouldn’t say it has not come to pass, only that much has come in between. I am no longer married to X, for instance. The child we had when everything was starting has died, though there are two others, as I mentioned, who are alive and wonderful children.

Frank is a little like what Frank Wheeler, the male half of the couple in Revolutionary Road, would have become if he’d decided to give up on finding himself and embrace suburban conformity. We learn that Frank tried to write a novel, but gave up his literary ambitions in order to be a sportswriter for “a glossy New York sports magazine you all have heard of.” Throughout the novel he tells people he meets that they would make good sportswriters, with the “anyone can do it” cheerfulness with which people are now told to learn to code.

He wants the reader to know that the three big deaths — of his novel, his marriage, and his child — have not made him feel sorry for himself. He gives us his maxim: “If sportswriting teaches you anything, and there is much truth to it as well as plenty of lies, it is that for your life to be worth anything you must sooner or later face the possibility of terrible, searing regret. Though you must also manage to avoid it or your life will be ruined.”

He believes it’s possible to do both — both face regret and avoid it — but over the course of the book we come to wonder if, truly, he has managed either one. Frank has a number of ways to cope, some of which would not be out of place in self-help books about managing depression. His method involves feeling grateful for life’s small pleasures, anticipating good things to come (even if the specifics are a bit nebulous), and to avoid overthinking, especially about the past. But he also lays out the implications of this approach to life, which are not hopeful but absolutely brutal:

If there’s another thing that sportswriting teaches you, it is that there are no transcendent themes in life. In all cases things are here and they’re over, and that has to be enough. The other view is a lie of literature and the liberal arts, which is why I did not succeed as a teacher, and another reason I put my novel away in the drawer and have not taken it out.

Oof.

Frank admires the tranquility of mind he recognizes in the athletes he writes about, who are “never likely to feel the least bit divided, or alienated, or one ounce of existential dread.” But he also recognizes the fragility of this state of mind, how easy it is to spoil it:

Years of athletic training teach this; the necessity of relinquishing doubt and ambiguity and self-inquiry in favor of a pleasant, self-championing one-dimensionality which has instant rewards in sports. You can even ruin everything with athletes simply by speaking to them in your own everyday voice, a voice possibly full of contingency and speculation. It will scare them to death by demonstrating that the world — where they often don’t do too well and sometimes fall into depressions and financial imbroglios and worse once their careers are over — is complexer than what their training has prepared them for. … And if you are a sportswriter you have to tailor yourself to their voices and answers: “How are you going to beat this team, Stu?” Truth, of course, can still be the result — “We’re just going out and play our kind of game, Frank, since that’s what got us this far” — but it will be their simpler truth, not your complex one.

As someone who is a ruminator and overthinker and prone to existential dread — as I suspect many of you are — it’s tempting, exceedingly tempting, to wish for the ability to shut off this part of the mind, and revert to simplicities like just going out and playing our kind of game. Frank finds it not only tempting but advisable, and we see him trying to bring himself as close to that state as possible. He’s endlessly aware of things that might spoil his mood, or ruin his day, and tries to forestall and avoid them as much as he can. And the thing with the most power to ruin his day, we see, is a difficult, emotional conversation with another human.

Some of you might recognize in Frank the men you know, especially of a certain generation, in their protective approach to conversation and emotions. Most of them don’t write breathtakingly beautiful prose, or observe others with as much acuity and warmth as Frank. And herein lies his contradiction. He writes about the people he knows warmly, even affectionately, with psychological insight and an eye for detail. He fantasizes about close friendships with other men, the kind where you go on fishing trips and get drunk at Red Lobster and argue about who you like in the championship. But the kind of friendship where you bare your soul? He flees.

The first person who tries to bare his soul to Frank is a casual friend of his, Walter, whose wife has recently left him to live on a tropical island with a waterski instructor. Walter is desperate for a confidante, and having seen Frank’s book of short stories, thinks he might be a good, non-judgmental listening ear. But when he makes his confession to Frank — that he has had sex with a man for the first time, and is wracked with shame and guilt — Frank can’t get away fast enough.

The second is the prospective subject of one of Frank’s pieces for the glossy magazine, a former NFL lineman named Herb who has suffered an injury and is now confined to a wheelchair. Frank is hoping to write an inspirational piece, grit and survival and so on, but when he arrives to interview Herb he discovers that the man only wants to talk about death. Herb is furious when he realizes that Frank is ducking the conversation — “God damn it! You haven’t even taken any notes yet!” — and when he pushes harder to explain the truth of his feelings, once again, Frank flees.

Of course, he has other ways of evading painful conversations, including that old male standby: talking about sports, a skill in which his expertise is deep and finely honed. It is both an escape hatch and a shortcut to camaraderie. Late in the book we see him evade a difficult conversation by proposing a game of croquet.

If what he wants from men is companionship, of the Red Lobster kind that can never be dark or frightening, what he wants from women is solace, tenderness. “Women have always lightened my burdens, picked up my faltering spirits and exhilarated me with the old anything-goes feeling,” he says, “though anything doesn’t go, of course, and never did.” He gives us a glimpse of a fantasy relationship: one where you meet a stranger in a bar, dive deep into conversation, “woggle the bejesus out of each other” in a hotel room (this phrasing made me laugh out loud), and then think of each other fondly but never meet again. He especially prizes what he calls mystery in women, and also prizes it in life, attaching to the idea a kind of beautiful anticipatory weightlessness, something whose promise is unspoiled.

We meet several of his women, principally among them his ex-wife (referred to simply as X) and his young girlfriend, Vicki Arcenault. Vicki seems so clearly a figure out of male fantasy: a pretty, unsophisticated and easygoing nurse from Texas, always sweet and full of affection, always up for anything. He thinks he has found his counterpart in her, someone who knows how to be happy by skating cleanly across the surface of life. I confess I found myself frequently rolling my eyes at Vicki, whose aw-shucks cheeriness strains credulity at times and whose vocabulary includes expressions like “boy-shoot” and “no-ho way” and “ole gloomy-doomy.” He wants to marry her, but we sense that his feeling for her is no deeper than that wish for comfort. Early on, when she tells a story about the death of her mother, he can think only of how her story has spoiled his mood.

The women, though they are drawn to him, can sense after a time what’s missing in him, and recoil. Herb the lineman senses it too. “When I first saw you, you had a halo around your head. A big gold halo. Do you ever notice that, Frank?” Later he informs him that the halo has disappeared.

Some of the blurbs from the book on the inside cover seem to take Frank’s advocacy for his way of life at face value. “An appreciation of the mystery of things as they are,” says Time. “Suffused with love for small, fleeting mysteries of life,” says New York. The back cover describes the novel as a “portrait of heroic decency” and perhaps it is that, but in its pages I sense something much more complex, more ironic and sad. Are we meant to take Frank at his word? Is he happy?

He’s avoiding that question. He doesn’t want to know.

At the risk of being one of the men who is reminded of and recommends DFW in response to pretty much anything, I'm reminded of and recommend DFW's essay "How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart" for more on the frustrating, inarticulate dream state of high-end athleticism.

Ahh now I want to read this. I've been following your mid-life crisis in suburbia binge, may I recommend Julian Barnes' The Sense of an Ending? He's so brilliant on how life incrementally becomes what you didn't really hope for -- how you settle in to a life, and possibilities narrow down. Also, one of the stories in Zadie Smith's Grand Union, 'Miss Adele Amidst the Corsets'.